Today, the ability to keep track of time seems to be taken for granted. One just simply needs to glance at a watch, clock, or mobile phone to know the exact time, even down to the nearest second. Prior to the invention of such battery-operated gadgets, timekeeping was done quite differently. In the ancient world, for instance, sundials were commonly used. This method of measuring time, however, had its flaws. Sundials would, of course, only function when there was sunlight, and they could not maintain a constant division of time. To compensate for these shortcomings, the water clock was invented. Although no one is certain when or where the first water clock was made, the oldest known example is dated to 1400 BC, and is from the tomb of the Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep III.

In the ancient world, there were two forms of water clocks: outflow and inflow. In an outflow water clock, the inside of a container was marked with lines of measurement. The container was filled with water, which was allowed to leak out at a steady pace. Observers were able to tell time by measuring the change in water level. An inflow water clock followed the same principle as an outflow one, i.e. the steady dripping of water. Unlike the latter, the former’s measurements were in a second container instead. Based on the amount of water that dripped from the first container, one was able to tell how much time had passed.

Ancient Water Clock of Karnak

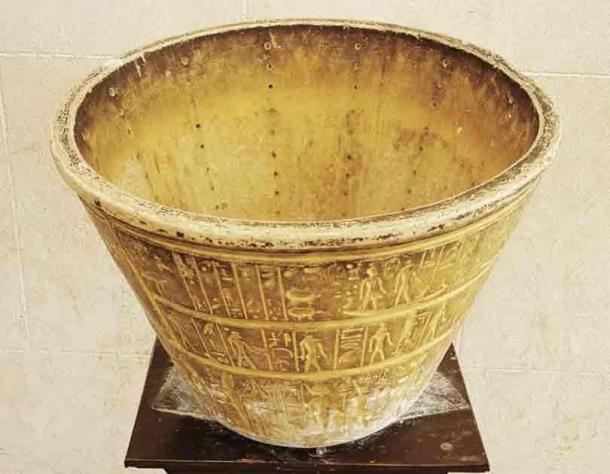

The most ancient water clock with tangible proof traces back to approximately 1417–1379 BC, dating back to the rule of Amenhotep III, when it was employed within the Temple of Amen-Re at Karnak. The earliest recorded mention of the water clock is found in the tomb inscription of court official Amenemhet, from the 16th century BC Egypt.

The Clepsydra of Karnak, now at the Egypt Museum. (Egypt Museum)

The Karnak Clepsydra was discovered fragmented, crafted from alabaster. Its design resembles that of a sizable flowerpot, featuring distinctive depictions arranged in three horizontal rows on the exterior, along with a vignette portraying King Amenhotep III.

The water clock features 12 carved columns with 11 spaced markings, representing the hours of the night. Water trickled through a minute hole positioned at the center of the bottom, emerging externally beneath a seated figure of a baboon. To tell the time, individuals would peer into the basin, noting the water level and determining the time based on the closest spaced marking.

Introduction to Water Clocks in Ancient Greece

Around 325 BC, water clocks began to be used by the Greeks, who called this device the clepsydra (‘water thief’). One of the uses of the water clock in Greece, especially in Athens, was for the timing of speeches in law courts. Some Athenian sources indicate that the water clock was used during the speeches of various well-known Greeks, including Aristotle, Aristophanes the playwright, and Demosthenes the statesman. Apart from timing their speeches, the water clock also prevented their speeches from running too long. Depending on the type of speech or trial that was going on, different amounts of water would be filled into the vessels.

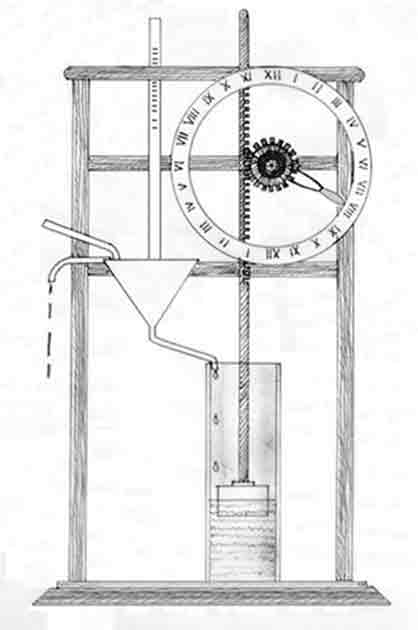

Illustration depicting a clepsydra clock, characterized as an automaton or self-regulating apparatus. Upon water entry, a figurine ascends and indicates the current hour of the day. Excess water triggers a mechanism of gears, facilitating the rotation of a cylinder to adjust the hour durations according to the present date. The ancient Greeks and Romans had twelve hours from sunrise to sunset. Due to the variation in day lengths between seasons, summer hours were lengthened compared to winter hours. (Public Domain)

The water clock, however, was not without its flaws. First of all, a constant pressure of water was needed to keep the flow of water at a constant rate. To solve this problem, the water clock was supplied with water from a large reservoir in which the water was kept at a constant level. An example of this can be seen in the ‘Tower of the Winds’ which was built by the Greek astronomer Andronikos in Athens during the 1st century BC. Still standing, it is an octagonal marble structure 42 feet (12.8 m) high and 26 feet (7.9 m) in diameter.

Each of the building’s eight sides faces a point of the compass and is decorated with a frieze of figures in relief representing the winds that blow from that direction; below, on the sides facing the sun, are the lines of a sundial. The Horologium was surmounted by a weather vane in the form of a bronze Triton and contained a water clock (clepsydra) to record the time when the sun was not shining.

The Tower of the Winds was built by the astronomer Andronikos in the 1st century BC and is located at the Roman Agora of Athens. It was a water clock, sundial, and weathervane. (George E. Koronaios/CC BY-SA 2.0)

Seasonal Calibration of Water Clocks

Another problem with the water clock was that as the length of day and night varied with the seasons, it was necessary for the clocks to be calibrated each month. Several solutions were employed to counter this problem. For instance, a disc with 365 holes of varying sizes was used to regulate the flow of water. The largest hole corresponded to the winter solstice, as the day would be shortest, while the smallest hole corresponded to the longest day of the year, the summer solstice. These two holes were at opposite ends of the disk, with the other holes arranged between them in increasing or decreasing sizes. The holes corresponded to the days of the year and would be rotated by one hole at the end of each day.

Although the fundamental principle of the water is a relatively simple one, there were some challenges related to the physics of water pressure and the changing seasons that the ancients had to deal with, resulting in the water clocks becoming more and more complex over time. When compared to the ease at which we keep track of time today, it seems that we have come quite a long way.