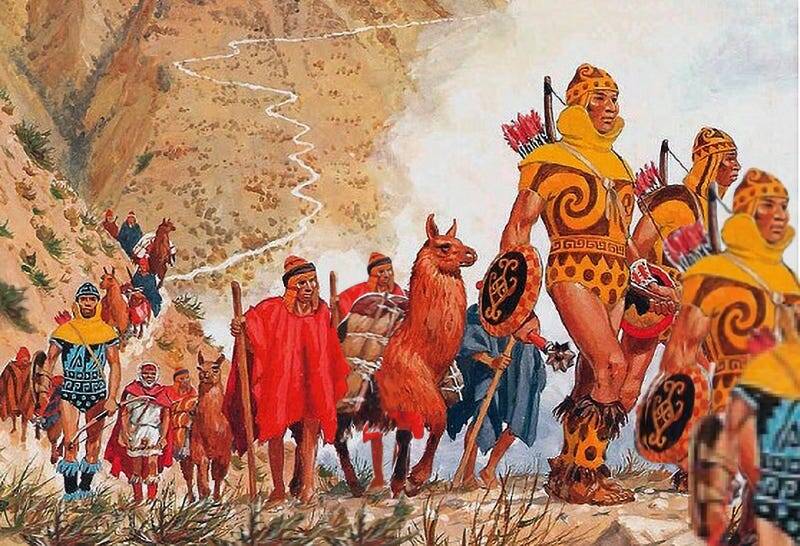

The Inca Empire was the largest in the world in the 16th century, but the arrival of Francisco Pizarro and the defeat of emperor Atahualpa in 1532 rapidly brought it to an end.

Public DomainA 16th-century illustration of the Inca fighting the Spanish.

In 1533, the Inca Empire was the largest in the world. Stretching from modern-day Chile to Ecuador, it included more than 10 million people who spoke at least 30 different languages. But by the end of the century, it had all but vanished. So, how did the Inca Empire fall so quickly?

By the time Spanish conquistador Francisco Pizarro and his army of men arrived on the coast of Ecuador in 1531, the Incas were already suffering from diseases brought by the Spanish that had spread from other parts of the Americas. They were also in the midst of a civil war brought about by a dispute over succession.

So, when Pizarro marched into the Inca city of Cajamarca in November 1532 and captured emperor Atahualpa, it only hastened the decline of the Inca Empire. Indeed, many historians mark 1533 — the year Atahualpa was killed and the Spaniards conquered the capital city of Cuzco — as the end of the civilization.

Still, the final Inca ruler, Túpac Amaru, didn’t die until 1572. By then, however, the ill-fated empire was in a downward spiral that there was no coming back from.

The Legendary Origins Of The Inca Empire

Public DomainA portrait of Urco, the ninth Inca king.

The story of the Inca Empire begins with Ayar Manco.

According to legend, Ayar Manco and his siblings set out in search of fertile land equipped with a golden staff that would sink into the ground when they reached their final destination. There, they were to build a temple to their Sun god, Inti.

Ayar Manco was the only sibling left alive by the end of the journey, and he founded the Inca Empire in the Valley of Cuzco. There, he took the name Manco Cápac, or King Manco. Today, he is recognized in both Incan mythology and by some historians as the founder of the Kingdom of Cuzco in the early 13th century.

After Manco Cápac’s reign, the Inca had eight kings whose rules have been lost to history. The next king to appear in the historical record was Cusi Yupanqui, or Pachacuti, in the 1400s. Under his rule, the empire’s territory expanded both north and south, encompassing modern-day Ecuador, Chile, Bolivia, Colombia, Argentina, and Peru.

Public DomainMuch of the Incan territory was mountainous, and the slow movement of important messages throughout the domain partially contributed to the empire’s downfall.

He encouraged the integration of nearby territories into his own and built a federalist system from the ground up. The Kingdom of Cuzco was portioned into four parts, each with provincial governors beholden to the king and paved highways connecting them.

Under Pachacuti’s rule, the Kingdom of Cuzco built Machu Picchu, likely as a royal estate for his family, as well as other impressive structures.

Lukas Uher / Alamy Stock PhotoThe Incan city of Machu Picchu.

At the empire’s height, the Kingdom of Cuzco had transformed into the Inca Empire with a formidable military force, sprawling territory, and well-organized governmental structures that protected over 10 million people.

However, that would all come to an end within a century.

The Spanish Arrive In Inca Territory

The story of how the Inca Empire fell begins with Spanish conquistador Francisco Pizarro setting sail for the New World on Nov. 10, 1509. From 1519 to 1523, Pizarro was the mayor and magistrate of the newly founded Panama City.

In 1522, the first reports of the Inca fell on Spanish ears. Explorer Pascual de Andagoya traveled south and made contact with several Indigenous chiefs. They told Andagoya about a land to the south rich in gold. The stories intrigued Pizarro, and soon, he began organizing expeditions to track down this mysterious civilization.

Public DomainOne of the first European depictions of the Inca, circa 1553.

In November 1524, Pizarro left for his first expedition alongside 80 men and four horses. However, bad conditions forced him to turn back after reaching modern-day Colombia.

Pizarro tried again two years later, this time making it as far south as Peru. Although he did not make contact with higher-up Inca officials during the second expedition, Pizarro saw firsthand the wealth of the Inca Empire in its northern territories and resolved to make it to the heart of the civilization soon.

Then, in 1530, Pizarro embarked on his third expedition. By Nov. 15, 1532, Pizarro and his crew had arrived in Cajamarca in northern Peru. There, the Inca emperor Atahualpa received word of Pizarro and his league of men and horses, or “large llamas,” as the Inca king’s aids stated. Curious about Pizarro, Atahualpa agreed to meet with him at his palace fortress in Cajamarca.

According to a 1533 letter from Hernando Pizarro, the half-brother of Francisco Pizarro, Atahualpa was very interested in seeing the Spaniards:

After seven or eight marches, a captain of Atahualpa came to the Governor and said that his lord had heard of his arrival and rejoiced greatly at it, having a strong desire to see the Christians; and when he had been two days with the Governor he said that he wished to go forward and tell the news to his lord, and that another would soon be on the road with a present as a token of peace.

With an army of over 50,000 warriors, Atahualpa did not fear Pizarro or his men. Instead, he likely viewed the meeting as a spectacle. This error in judgment would ultimately lead to the Inca Empire’s downfall.

How Did The Inca Empire Fall?

On Nov. 16, 1532, Pizarro and his men preemptively hid themselves in the Inca stone fortress in Cajamarca ahead of their meeting with Atahualpa.

That day, Atahualpa arrived at the fortress with thousands of Inca soldiers. Immediately, the Spanish sent a friar, Vincente de Valverde, to read the requerimiento to the monarch. This was a legal document created to give Indigenous people a chance to submit to Spanish rule before forcibly losing their territory. According to the National Library of Medicine, part of it read:

Wherefore, as best we can, we ask and require you that you consider what we have said to you, and you take the time that shall be necessary to understand and deliberate upon it, and that you acknowledge the Church as the ruler and superior of the whole world, But if you do not do this, and maliciously make delay in it, I certify to you that, with the help of God, we shall powerfully enter into your country, and shall make war against you in all ways and manners that we can, and shall subject you to the yoke and obedience of the Church and of their highnesses.

To this demand, Atahualpa allegedly replied: “I will be no man’s tributary.” With these words, the hidden Spanish soldiers fired on the Inca. In the midst of the sudden chaos, the Spanish seized Atahualpa. The Battle of Cajamarca resulted in the loss of 2,000 Inca soldiers, counselors, and other attendees at the fortress.

On Aug. 29, 1533, Atahualpa was executed via garrote. After his death, Pizarro marched on Cuzco with an army of 500 men on Nov. 15, 1533, almost a year to the day after he’d captured Atahualpa.

Public DomainA painting depicting the Battle of Cajamarca, when Pizarro captured emperor Atahualpa, marking the beginning of the end for the Inca Empire.

Over the next several years, various Inca chiefs would rebel against Spanish rule, but none were successful at preventing them from tightening control over the region. The Spanish also benefited from the spread of the deadly smallpox virus that killed an estimated 50 to 90 percent of the Inca population.

By 1572, the Spanish had conquered the last Incan stronghold by capturing and killing Túpac Amaru, the final Inca ruler.

From then on, the Spanish systematically destroyed many aspects of Inca culture, replacing their temples with churches and forcing them to work in gold and silver mines. So, how did the Inca Empire fall? Just as it rose: quickly.