Human sacrifice was practiced in many early human societies throughout the world. In China and Egypt the tombs of rulers were accompanied by pits containing hundreds of human bodies, whose spirits were believed to provide assistance in the afterlife.

Ritually slaughtered bodies are found buried next to rings of crucibles, brass cauldrons and wooden idols in the peat bogs of Europe and the British Isles. Early explorers and missionaries documented the importance of human sacrifice in Austronesian cultures, and occasionally became human sacrifices themselves.

In Central America, the ancient Mayans and Aztecs extracted the beating hearts of victims on elevated temple altars. It is no surprise, then, that many of the oldest religious texts, including the Quran, Bible, Torah and Vedas, make reference to human sacrifice.

This raises some key questions: how and why could something as horrifying and costly as human sacrifice have been so common in early human societies?

Is it possible that human sacrifice might have served some social function, and actually benefited at least some members of a society?

Social control?

According to one theory, human sacrifice actually did serve a function in early human societies. The Social Control Hypothesis suggests human sacrifice was used by social elites to terrorize underclasses, punish disobedience and display authority. This, in turn, functioned to build and maintain class systems within societies.

My colleagues and I were interested in testing whether the Social Control Hypothesis might be true, particularly among cultures around the Pacific.

So we gathered information on 93 traditional Austronesian cultures and used methods from evolutionary biology to test how human sacrifice affected the evolution of social class systems in human prehistory.

Canoe-sarcophagus of the Dayak: a burial that recalls the Malagasy tradition that former Ntaolo Vazimba and Vezo buried their dead in canoe-sarcophagi in the sea or in a lake. (CC Y SA 3.0)

The ancestors of the Austronesian peoples were excellent ocean voyagers, originating in Taiwan and migrating west as far as Madagascar, east as far as Easter Island and south as far as New Zealand. This is an area covering more than half the world’s longitude.

These cultures ranged in scale from the Isneg, who lived in small, egalitarian, family-based communities, to the Hawaiians, who lived in complex states with royal families, slaves and hundreds of thousands of people.

Human sacrifice was performed in 43% of the cultures we studied. Events that called for human sacrifice included the death of chiefs, the construction of houses and canoes, preparation for wars, epidemic outbreaks and the violation of major social taboos.

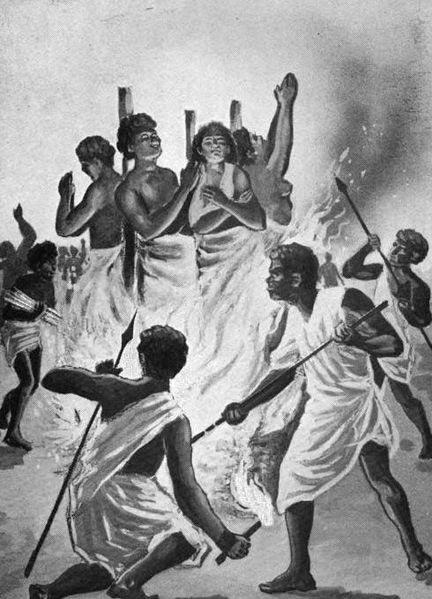

The physical act of sacrifice took a wide range of forms, including strangulation, bludgeoning, burning, burial, drowning, being crushed under a newly-built canoe, and even being rolled off a roof and then decapitated.

In Austronesia human sacrifice was common in cultures with strict class systems but scarce in egalitarian cultures. While an interesting correlation, this doesn’t tell us whether human sacrifice functioned to build social class systems, or whether social class systems led to human sacrifice.

Captain James Cook witnessed human sacrifice in Taihiti during his visit around 1773. 1815 edition of Cook’s ‘Voyages’/Wikimedia Commons

Good for the elites

Using what is known about the family tree of Austronesian languages and the data we collected on 93 traditional Austronesian cultures, we were able to reconstruct Austronesian prehistory and test how human sacrifice and social structures co-evolved through time.

This enabled us to not only test whether human sacrifice is related to social class systems, but also get at the direction of causality based on whether human sacrifice tends to arise before or after social class systems.

Our results show that human sacrifice tended to come before strict class systems and helped to build them. What’s more, human sacrifice made it difficult for cultures to become egalitarian again.

This provides strong support for the Social Control Hypothesis of human sacrifice.

In Austronesia, the victims of human sacrifice were often of lower status, such as slaves, and the perpetrators of high status, such as chiefs or priests. There was a great deal of overlap between religious and political systems and in many cases the chiefs and kings themselves were believed to be descended from the gods.

A Tagalog couple of the Maginoo (nobility) caste depicted in the 16th century Boxer Codex, Philippines. (Public Domain)

As such, the religious systems favored social elites, and those who offended them had a habit of becoming human sacrifices. Even when a broken taboo strictly required human sacrifice, there was flexibility in the system and punishment was not even-handed.

For example, in Hawaii, a person who broke a major taboo could substitute the life of a slave for their own, providing they could afford a slave. Human sacrifice could have provided a particularly effective means of social control because it provided a supernatural justification for punishment, its graphic and painful nature served as a deterrent to others, and because it demonstrated the ultimate power of elites.

The overlap between religious and secular systems in early human societies meant that religion was vulnerable to being exploited by those in power. The use of human sacrifice as a means of social control provides a grisly illustration of just how far this can go.

Illustration of Christian martyrs burned at the stake by Ranavalona I in Madagascar. (Public Domain)

Featured image: Hawaiian sacrifice, from Jacques Arago’s account of Freycinet’s travels around the world from 1817 to 1820. (Public Domain)