Four samurai texts dating back centuries have recently been translated into English, complicating Western notions about the practice of ritual suicide known as seppuku.

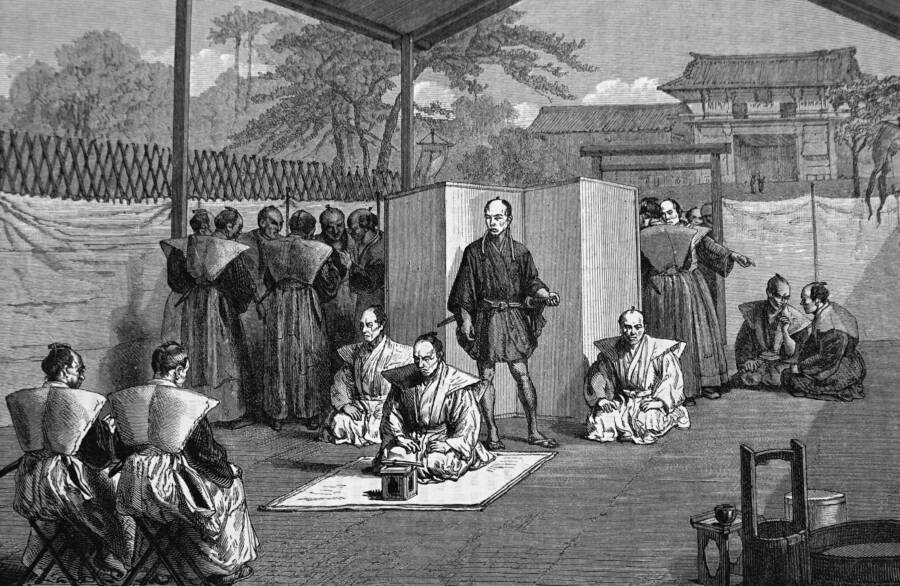

World History Archive/Alamy Stock PhotoA rendering of a seppuku ceremony, with the condemned samurai kneeling in the center.

Translator Eric Shahan recently published English-language versions of four centuries-old texts passed down by the samurai that detail how they carried out the suicide ritual of seppuku. Translated into English for the first time, these texts dispel many Western assumptions about seppuku, including the popular notion of a samurai stabbing himself in the stomach to take his own life.

The texts also reveal new information about the samurai way of life, including how a samurai’s rank could influence his death and what crimes were considered to be punishable offenses.

Newly Translated Samurai Texts Reveal Lesser-Known Details About Seppuku

Seppuku is a form of ritual suicide also referred to as harakiri in which a samurai could achieve a noble death or atone for his crimes by taking his own life. Commonly, it is associated with the practice of a samurai slitting his own abdomen, but according to the newly translated texts, this was largely not the case by the time of the Edo period (1603 to 1868).

Seppuku had instead evolved into a full ceremony by that point, one which ended with the beheading of the condemned man by another samurai. Elements of this ceremony are described in the recently translated texts, shedding some light on how the ritual played out and why it was carried out in the first place.

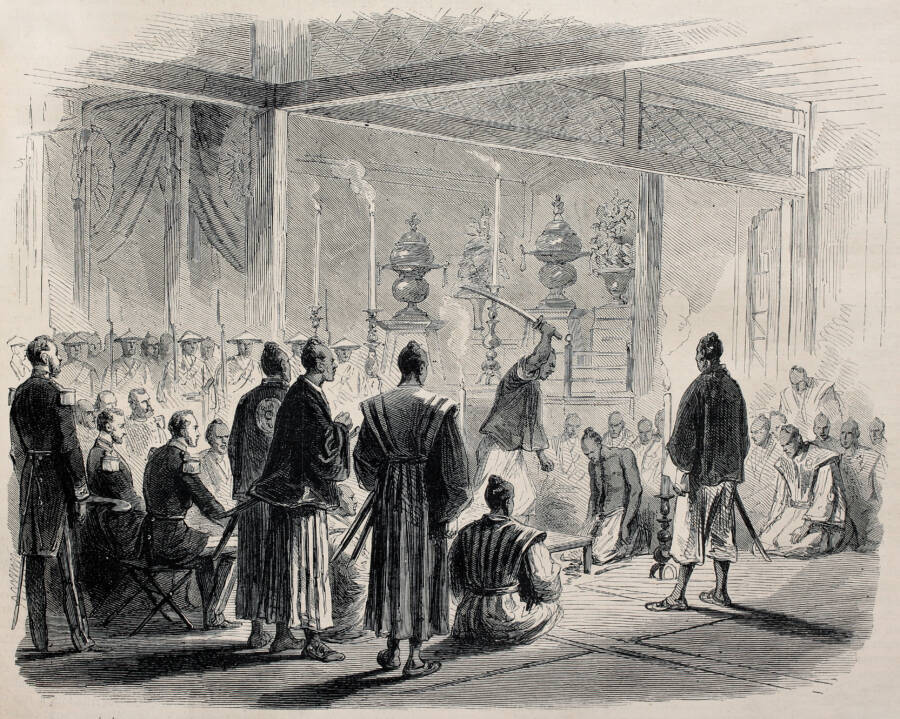

adoc-photos/Corbis via Getty ImagesA photographic reenactment of harakiri.

The earliest text, entitled “The Inner Secrets of Seppuku,” was written sometime during the 17th century and “contains secret teachings that are traditionally only taught verbally,” as the samurai Mizushima Yukinari writes, “however they have been recorded here so that these lessons will not be forgotten and Samurai can be prepared.”

Shahan, a third-degree black belt in Kobudo, has previously translated several Japanese martial arts texts, and has now self-published the newly translated texts in his book Kaishaku: The Role of the Second. The book comprises four texts: “The Inner Secrets of Seppuku,” “Secrets of Seppuku,” and two excerpts from larger works on sword drawing, both titled “Kaishaku Technique,” one from 1938 and one from 1940.

As Shahan explains, a kaishakunin, or “second,” is the person charged with assisting in the ceremony of seppuku. They were often the samurai who performed the beheading.

Universal Art Archive/Alamy Stock Photo

An illustration of Taki Zenzaburo dying by seppuku after the Kobe incident.

Many instructions in the ceremony align with the core concepts of bushidō, the strict code of honor by which the samurai lived. The three core themes of bushidō are honor, loyalty, and duty, and these themes present themselves in various ways.

For example, one of the newly translated texts, written in 1840 by the samurai Kudo Yukihiro, reads: “It is essential that you do not fail to notice first the eyes and then the feet of the person committing Seppuku. If you fail to do this due to a personal connection with the condemned, it will be proof that you have lost your martial bearing and bring down an eternal shame upon yourself.”

Wellcome Library, London/Wikimedia CommonsKoboto Santaro, a Japanese military commander, in his samurai armor.

Specific details of seppuku ceremonies varied, but as Shahan told Live Science, a common form of the ceremony involved giving sake to the condemned, then presenting him with a sharp knife. The condemned could use this knife to split open his stomach, though again, in the Edo period this was less common. Shortly after the knife was presented, the kaishakunin would decapitate the condemned.

Shahan explained that the relative peace of Edo period Japan made the samurai less skilled with blades than their forebears had been. As such, they were less prepared to perform harakiri properly.

Shahan’s translations also revealed new information about how rank influenced the seppuku ceremony.

Stark Differences In Seppuku Ceremonies Based On The Samurai’s Standing

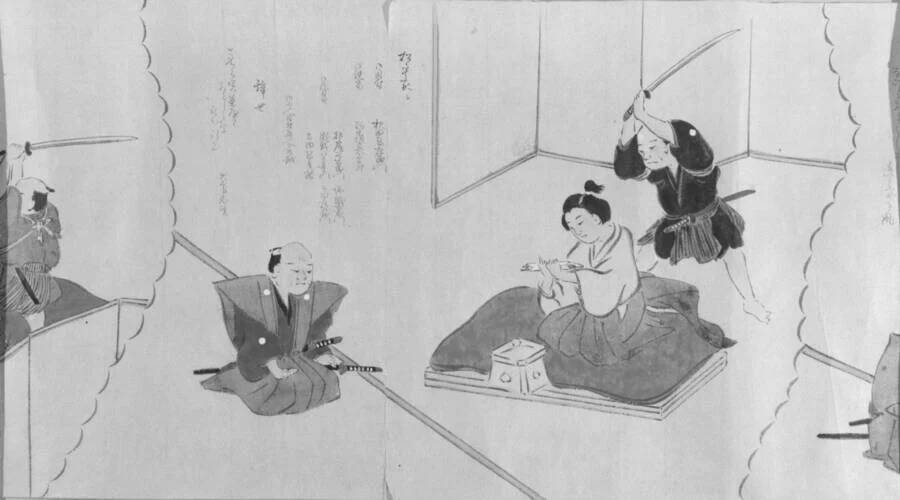

Brooklyn MuseumA 20th-century handscroll painting of a samurai awaiting his kaishakunin.

Samurai who abided by the core tenets of bushidō and rose through the ranks were treated with far greater reverence than those who did not — even when it came time for them to die.

An honorable samurai who chose to take his own life when his lord died, for instance, received a much higher level of treatment during the seppuku ceremony than a low-level warrior who committed a crime. The higher-status samurai could even dictate how the ceremony was carried out.

“The highest-ranking person to commit Seppuku is probably Oda Nobunaga, who committed Seppuku in 1582, after his retainer Akechi Mitsuhide betrayed him and attacked him at Honnoji Temple,” Shahan told Live Science. “Oda was a Daimyo, or lord of one of the hundreds of domains ruled by a powerful Samurai. He had been slowly eliminating his opponents and had succeeded in unifying Japan under his rule when he was betrayed.”

Wikimedia CommonsThe grave of Oda Nobunaga.

When Oda chose to die, he was vastly outnumbered, so it is unclear exactly how he went about the seppuku ceremony. Typically, a samurai of Oda’s rank would have had his hair perfumed after decapitation. His head would then have been wrapped in white cloth and placed in a box. However, given the circumstances, it’s possible he had foregone the sake-drinking and hair-perfuming aspects of the ritual.

Of course, not all samurai were given such favorable treatment. Samurai of low rank, or those who committed severe crimes, were often given the fourth-level treatment known as “yondan.” Samurai killed in this manner were bound before their head was cut off, and afterward they were simply thrown into a ditch, a far cry from the forms of seppuku that have lived on in the world’s imagination for the last several centuries.