The Bladen Journal reports that a mummified hand found in Castleton, North Yorkshire, England is the only known ‘Hand of Glory’, a grotesque artifact meant to aid thieves in their work during the night, still in existence. This mummified hand supposedly has the power to “entrance humans” according to the Express. Hands of Glory were also a favorite tool for thieves and creative storytellers for over 200 years.

What the newspapers have claimed as the last Hand of Glory was first uncovered in 1935 inside the wall at a thatched cottage in Castleton by a stonemason and local historian named Joseph Ford. Ford is said to have immediately recognized the importance of the hand as a supernatural tool, so he gave it to the Whitby Museum for safekeeping soon after the discovery.

The process to make a Hand of Glory was very specific, according to Sabine Baring-Gould (1873) in his work Curious Myths of the Middle Ages:

“The Hand of Glory .. is the hand of a man who has been hung, and it is prepared in the following manner: Wrap the hand in a piece of winding-sheet, drawing it tight, so as to squeeze out the little blood which may remain; then place it in an earthenware vessel with saltpeter, salt, and long pepper, all carefully and thoroughly powdered. Let it remain a fortnight in this pickle till it is well dried, then expose it to the sun in the dog-days, till it is completely parched, or, if the sun be not powerful enough, dry it in an oven heated with vervain and fern. Next make a candle with the fat of a hung man, virgin-wax, and Lapland sesame.”

A gallows-style gibbet near Bedford, England. (CC BY NC SA 2.0) After a man was hung some people believed his hand could be cut off to be used for magic, such as to make a Hand of Glory.

The origins make it not very surprising that a Hand of Glory was a grotesque artifact meant to aid thieves in their work during the night. Legends claimed that if thieves used the Hand of Glory as a candlestick to hold the lit candle made from the hung man’s fat (or in some versions lit the fingertips of the hand) then they could open any locked door and render all those within the house unconscious or paralyzed until they had completed their task.

Two ways the Hand of Glory could have been used. (Whitby Museum)

But why was the hand hidden in a wall? Perhaps for safekeeping – but not in the usual sense of the word. One option is that folk magic may be at work. In the past, items of clothing and other objects were concealed behind walls to protect the living from evil spirits. It may be a similar situation with the Hand of Glory.

It is also possible that this was a Hand of Glory hidden after (or before) a robbery. Hands of Glory were popular objects in literature from the 1700s – 1900s and the tales of these morbid objects is said to have spread “across Europe, from Finland to Italy and Western Ireland to Russia.”

The website of the Whitby Museum also says that “at least two (of the legends) were current in North Yorkshire, one relating to the Spital Inn on Stainmore in 1797 and the other to the Oak Tree Inn, Leeming, supposedly in 1824.”

The story of Spital Inn begins with an old woman asking the innkeeper to sleep on a chair downstairs at the inn (with the pretext that she had to leave early the next morning). The innkeeper agreed and then retired upstairs with his family to sleep. The only person that remained downstairs was a young maid.

Map showing The Spittle (later known as Spital) on Stainmore (1579) (Portsmouth University)

This young woman noticed something odd about the “old woman” and upon discreet observation noted men’s trousers were exposed beneath the hem of the husky “woman’s” dress. The maid told herself that this was not a person to be trusted and vowed to remain awake that night to watch over the suspicious character.

The man removed his dress and bonnet when he believed the young girl was asleep and approached her with the lit Hand of Glory, he waved it in front of her face said “Let those who are asleep be asleep and those who are awake be awake.” With that, the thief placed the hand on a table and turned away from the maid, he then opened the door to let his partner in.

At that moment the girl jumped up and shoved the man outside, closing and barring the door behind him. She hurried upstairs and tried to wake the family. Unfortunately, the Hand of Glory had done its work and they were all under a deep sleep.

Soon, the maid heard the men trying to break down the door so she returned downstairs and tried to blow out the lit Hand of Glory. Finding that she could not, she took some nearby skimmed milk (one of two options for extinguishing the Hand of Glory – the other being blood) and threw it over the hand.

As the flames were smothered, the family awoke and heard her cries below. They caught the thieves after a short pursuit. The men promised they would leave the family in peace if the Hand of Glory was returned. However, the thieves were denied their request and scarcely escaped with their lives when the innkeeper took his gun and shot at them.

The Hand of Glory Inn from the 1944 film ‘A Canterbury Tale.’ (Power and Pressburger)

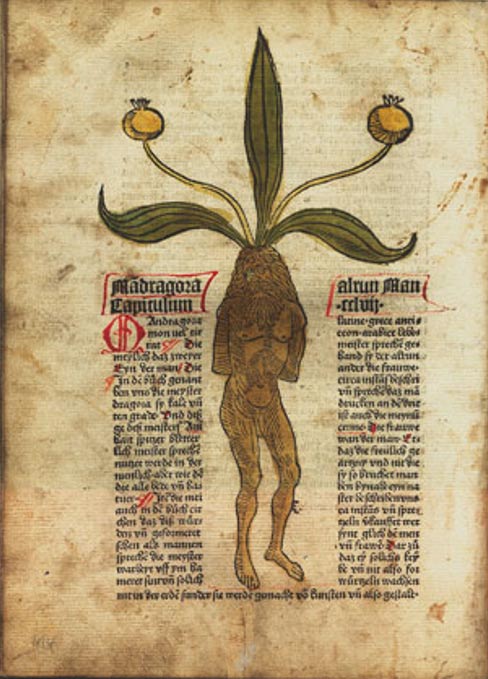

One final note of interest on the Hand of Glory is that the term may be derived from, main de gloire, which some scholars have said is a modification of the word mandrake, an herb which had various uses throughout history, including to incite madness, expel demons, and (especially useful for thieves) induce a deep sleep. The numerous stories and legends behind the Hand of Glory mean that if the Hand of Glory at the Whitby Museum really is the last of its kind, the preservation of the artifact is very important for history.

An image of a mandrake plant from a German text dating to 1485. (Public Domain)