Homer’s Iliad is often considered as one of the greatest works of Western literature. For many centuries, Homer’s Troy, the city besieged by the Greeks, was considered to be a myth by scholars. During the 19th century, however, one man embarked on a quest to prove that this legendary city actually existed. This was the German archaeologist, Heinrich Schliemann. He succeeded in his quest, and Hisarlik (the site where Schliemann excavated) is today recognized as the ancient site of Troy. Among the artifacts unearthed at Hisarlik is the so-called ‘Treasure of Priam’, which, according to Schliemann, belonged to the Trojan king, Priam.

Discovery of the Treasure of Priam

In 1871, Schliemann began excavating the site of Hisarlik. After identifying a level known as ‘Troy II’ as the Troy of the Iliad, his next objective was to uncover the ‘Treasure of Priam’. As Priam was the ruler of Troy, Schliemann reasoned that he must have hidden his treasure somewhere in the city to prevent it from being captured by the Greeks should the city fall. On the 31st of May 1873, Schliemann found the precious treasure he was seeking. In fact, Schliemann stumbled by chance upon the ‘Treasure of Priam’, as he is said to have had a glimpse of gold in the trench-face whilst straightening the side of a trench on the south-western side of the site.

A view of Schliemann’s Trench. (Winstonza/CC BY-SA 3.0)

A Golden Hoard

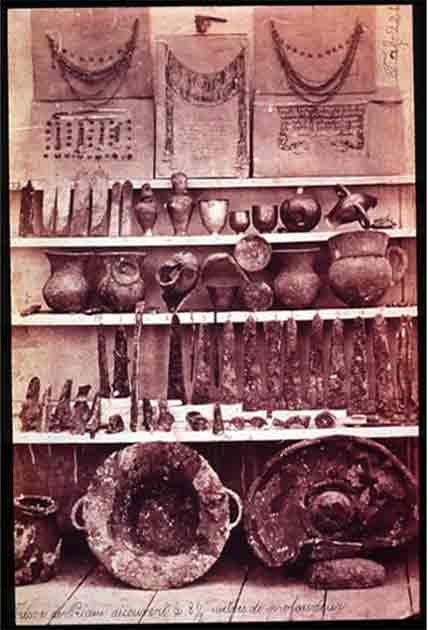

After removing the treasure from the ground (the objects were closely packed, and Schliemann reasoned that they had once been placed within a wooden chest which has since rotted away), Schliemann had his finds locked away in his wooden house. Apart from the gold and silver objects, the ‘Treasure of Priam’ included a number of weapons, a copper cauldron, a shallow bronze pan, and a bronze kettle. Although Schliemann reports that the ‘Treasure of Priam’ was a single find, others have doubted this claim, suggesting that it was a composite, in which the most important objects were discovered on the 31st of May 1873, whilst others were discovered at an earlier date, but nonetheless added into the treasure hoard.

Items from the Troy II treasure (“Priam’s Treasure”) discovered by Heinrich Schliemann (Public Domain)

Daring Plan To Keep The Treasure From Ottoman Hands

Regardless of the nature of the ‘Treasure of Priam’, the Ottoman authorities wanted to get their hands on the treasure. Schliemann, however, had other plans, and devised a plan to get the artifacts out of Ottoman territory. How Schliemann managed this feat is still a mystery, and there have been numerous speculations over the years. One legend, for instance, attributes Schliemann’s successful undertaking to his wife, Sophie, who smuggled the artifacts through Ottoman customs by hiding them in her knickers. Schliemann was eventually sued by the Ottoman government. He lost his case and was fined £400 as compensation to the Ottomans. Schliemann, however, voluntarily paid £2000 instead, and it has been pointed out that this increase probably secured him something extra, though what this was exactly is unknown.

Portrait of Sophia Schliemann wearing some of the Priam Treasures. It is believed she helped smuggle her husband’s find out of the country by hiding some of the treasures in her underwear. (Public Domain)

Finding A Home For Priam’s Treasure

After the discovery of the ‘Treasure of Priam’, Schliemann searched for a museum within which to display it. In the meantime, the valuable artifacts were being kept in Schliemann’s house, causing him much anxiety. It was in 1877 that the ‘Treasure of Priam’ made its first public display in London’s South Kensington Museum (now known as the Victoria and Albert Museum). After being displayed for several years in London, the ‘Treasure of Priam’ was then moved to Berlin in 1881. Between 1882 and 1885, the artifacts were temporarily displayed in the Kunstgewerbe Museum, before being transferred to the newly built Ethnological Museum.

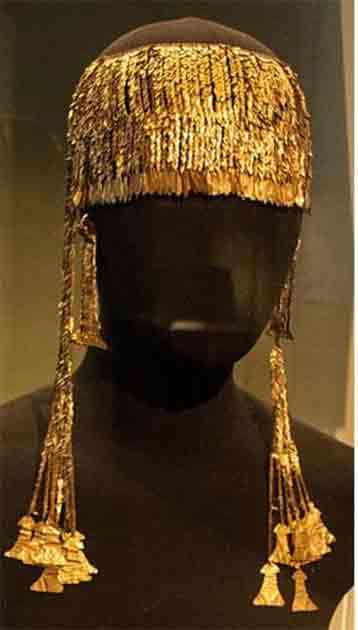

One of the prize treasures of the Priam hoard. Golden diadem with pendants in the shape of “idols” (Public Domain)

In the following decades, the ‘Treasure of Priam’ resided in Berlin’s Ethnological Museum. Following the defeat of Nazi Germany and the end of World War II in 1945, however, the artifacts disappeared. It has been suspected that the Soviet troops occupying Berlin were responsible for removing the treasure, as well as countless other valuable artifacts and artwork, to Moscow. Possession of the ‘Treasure of Priam’ was denied by the Soviets until 1993, when it was first admitted officially that the treasure was indeed in Russia. Today, the ‘Treasure of Priam’ is still residing in Russia. Whilst the Russians see the treasure as war booty to compensate for their losses during World War II, the Germans view it as looted goods, and demand its return.