Archaeologists have long been preoccupied with understanding the origins of metal coinage and monetization. Now, a team working in the Henan Province of China has discovered an early minting site at Guanzhuang, complete with Chinese spade coins and their clay molds. Experts have dated the site to 2,600 years ago, making this the oldest known coin mint in the world.

Map showing location of the Guanzhuang where the Chinese coin minting site was discovered. (H. Zhao / Antiquity Publications Ltd)

On Uncovering Chinese Coins at Guanzhuang

The archaeological site at Guanzhuang, just to the west of Zhengzhou, was an ancient city and important center of the Zheng state which covered a vast area composed of an inner city surrounded by a moat and a larger outer city. Established in about 800 BC, it was then abandoned around 450 BC. Guanzhuang has been undergoing excavations since 2004, during which time archaeologists have unearthed remnants of a pottery workshop and a copper casting workshop.

Excavations between 2015 and 2019 have also uncovered a bronze foundry. A new article published in Antiquity, describes their findings, which include evidence that the foundry was used to cast “exquisite ritual vessels, decorative chariot fittings, musical instruments, weapons and other elite goods” from about 770 BC. Nevertheless, the aspect which has captured their excitement is uncovering dozens of Chinese coin molds, coin fragments and discarded metal debris.

Spatial distribution of the minting remains in the foundry’s excavation area: red dots: deposit with clay moulds; green dots: deposits with fragments of finished spade coins. (Z. Qu / Antiquity Publications Ltd)

Is a Spade Really a Spade, or is it a Chinese Coin?

To be clear, the Chinese coins discovered at the site are not what you would imagine and recognize as money. In an article which discusses ancient Chinese currency, the National Museum of American History asks: “But what if that value was represented by something else, by something that looks like an everyday tool—like a phone, a pen, or a calculator? Ladies and gentlemen, I give you knife, spade, and bridge money!”

While currency in ancient China first took the shape of cowrie shells, by about 770 BC, metal formed into different shapes began to be used as currency. This included knife, spade and bridge money. “These coins were derivative productions of agricultural tools… that would have been bartered with in ancient China,” explains the NMAH.

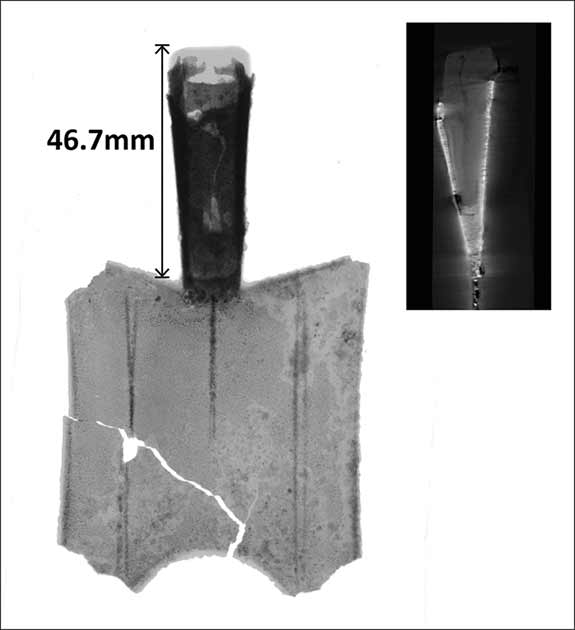

CT image of coin SP-1, one of the Chinese spade coins discovered in Guanzhuang. (H. Zhao / Antiquity Publications Ltd)

The Chinese coins discovered at Guanzhuang are known as spade coins. These are metallic objects shaped like a spade, and often marked with the name of the place it was produced or the authority in power at that time. Over time these spade coins became increasingly stylized and smaller in size, until they came to resemble what we call coins today.

Chinese Spade Coin Mint at Guanzhuang

The bronze foundry at Guanzhuang covers a large area within the outer enclosure just outside the southern gate of the inner city. At the foundry site, archaeologists have discovered over 2,000 pits which were used to dump the waste generated during coin production. These pits are a goldmine for archaeologists, as they are filled with all kinds of so-called trash, such as bits of ceramic and discarded remnants of bronze-casting production.

An aerial view of the foundry at Guanzhuang (Hao Zhao / Antiquity Publications Ltd)

These “crucibles, ladles, bronze droplets, unfinished or broken bronze artefacts, clay molds, charcoal, and furnace fragments” are helping archaeologists piece together the history of coin production at Guanzhuang. They have also found fragments of spade coins, clay cores and evidence of their manufacture. “The high degree of standardization of spade coins minted at Guanzhuang is reflected in the morphological uniformity of the clay cores,” explains the study published in Antiquity.

Analysis of findings from the Guanzhuang foundry covered the “full spectrum of remains related to spade-coin production, including finished coins, outer molds and used and unused clay cores.” Of particular interest was the finding of fragments of two finished spade coins. In one of the waste pits, the team uncovered coin SP-1, which allowed them to reconstruct the shape of the Chinese coin. It would have measured 143 mm in length, and 63.5 mm in width. Another coin labelled SP-2 was also discovered.

Unused clay cores for casting Chinese spade coins and coin SP-2. (H. Zhao/ Antiquity Publications Ltd)

The World’s Oldest Minting Site

The nature of the remains at the Guanzhuang foundry has allowed the archaeologists to perform radiocarbon-dating at the site. Combined with analysis of the mold style and ceramic typology, the study concluded that the foundry was established around 780 BC, while the minting workshop began producing coins some time around 640 to 550 BC.

It’s extremely rare to find a mint at such a rich archaeological site that provides evidence able to allow for precise dating. “Early minting sites are rarely found within well-documented archaeological contexts,” explains the study. Early coinage is usually discovered outside of its production context, such as in the frequently publicized hoards uncovered around the world.

The finding of Chinese coins within the context of their production is exception, especially when faced with such a staggering amount of evidence. The ability by the team to do “systematic AMS radiocarbon-dating of secure contexts” and therefore establish the timeframe from 640 to 550 BC, means that Guanzhuang is currently “the world’s oldest known, securely dated archaeological minting site.”

Questions still remain about who exactly was controlling the production of Chinese coins at Guanzhuang, and the archaeologists still have not been able to determine whether it was managed by merchant groups, the Zheng State, or some local authority. They have however concluded that “the production of spade coins was not a small-scale, sporadic experiment, but rather a well-planned and organized process in the heartland of the Central Plains of China.” What this could mean for understanding the history of currency, money and coinage, remains to be seen.