In a groundbreaking archaeological discovery, researchers have uncovered Europe’s earliest evidence of familial embalming at the Château des Milandes in Dordogne, France. The finding sheds light on the aristocratic Caumont family’s burial practices during the 16th and 17th centuries. This remarkable breakthrough not only highlights the sophistication of early modern European embalming techniques but also reveals their cultural and ceremonial significance.

Historical Context

The Caumont family, one of France’s most prominent aristocratic lineages, played a pivotal role in shaping early modern European society. Embalming practices, typically associated with ancient Egypt or South America, were rare in Europe. However, for the Caumont family, embalming symbolized their elevated social status. These procedures ensured that deceased family members could be displayed during elaborate funeral rituals, reinforcing their legacy and influence.

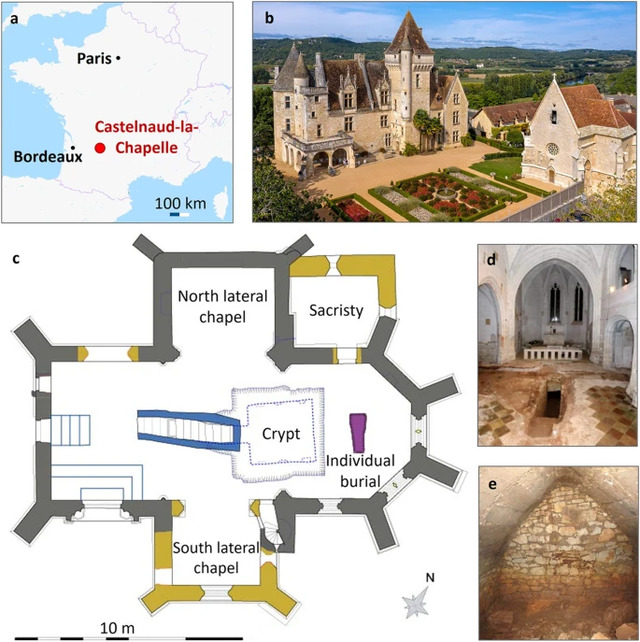

The Château des Milandes: A Landmark in Castelnaud-la-Chapelle, Dordogne, France

Unlike the Egyptians’ pursuit of long-term preservation, European embalming focused on delaying decomposition for public ceremonies and transportation. This discovery at Château des Milandes underscores the ceremonial role embalming played in early modern France, a practice previously documented only in historical texts.

Archaeological Findings

Excavations at the Château des Milandes crypt began in 2017, revealing scattered skeletal remains of the Caumont family. In 2021, researchers uncovered the grave of an elderly woman buried separately, further emphasizing the longevity and importance of embalming within this lineage.

Preserved in Time: Individual Burial ML2021 As Found During Excavation

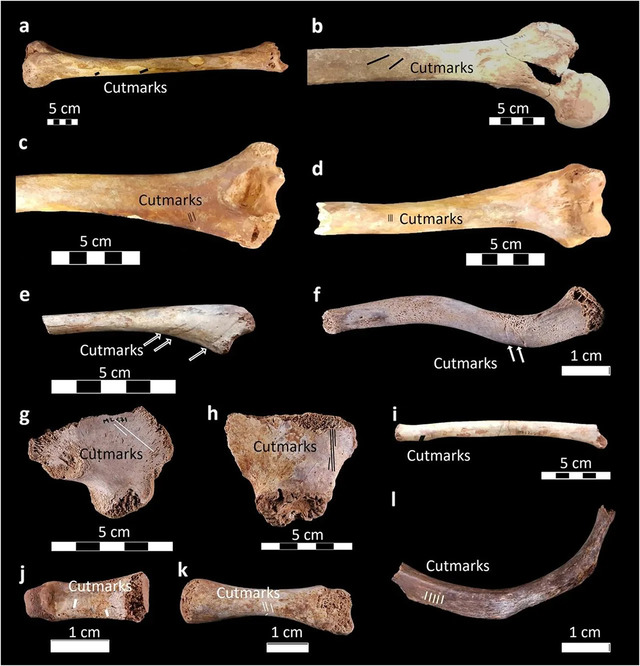

The remains included seven adults, five children, and the elderly woman, showcasing a rare application of embalming across all age groups. Researchers meticulously reconstructed skeletons from nearly 2,000 fragments, identifying precise cut marks on bones. These marks indicated a highly standardized process, reflecting embalming knowledge passed down for over two centuries.

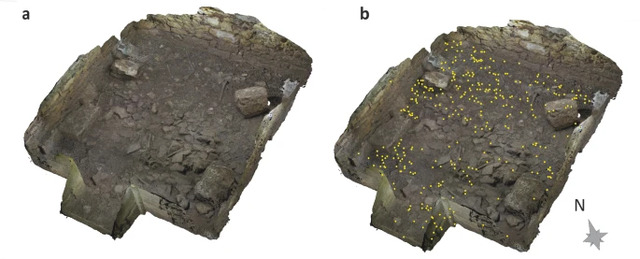

Insights from Excavation: (a) An Ongoing Phase; (b) Digital Documentation of Artifacts in Context

The Embalming Process

Detailed examinations revealed the intricate steps involved in the Caumont family’s embalming process:

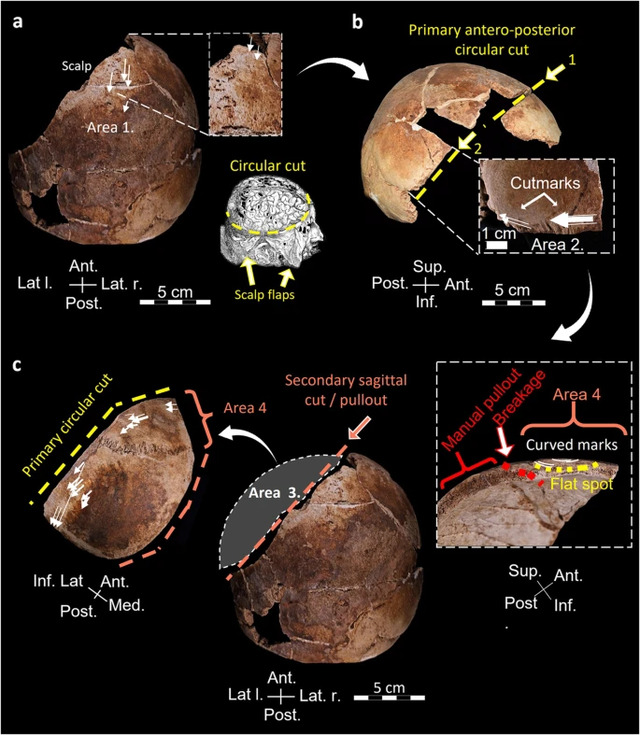

Skin Removal: The entire body, including limbs, fingertips, and toes, was skinned to prevent rapid decomposition. Organ Extraction: Internal organs, including the brain, were carefully removed to further slow decay. Filling Cavities: Empty cavities were packed with balsamic and aromatic substances, such as resin and herbs, to delay decomposition and mask odors.

These methods closely align with descriptions by Pierre Dionis, a prominent French surgeon of the early 18th century. His records from an autopsy in Marseille in 1708 detailed similar techniques, providing valuable context for the practices observed in the Caumont family crypt.

Fragments of the Past: A Skull Thought to Have Been Altered to Remove the Brain

Evidence of Embalming: Marks Found on Postcranial Bones Across Ages

Significance of the Findings

This discovery is unprecedented in European archaeology. While embalming has been documented in the Medici family crypt in 15th-century Italy, the Caumont family’s practice of embalming entire families, including children, is unique. This highlights the importance of status and lineage in early modern France, where even the youngest family members were included in these elaborate rituals.

The findings also illustrate the ceremonial nature of European embalming. Unlike the Egyptians, who sought eternal preservation, the Caumonts used embalming to temporarily preserve their loved ones for funeral displays. This practice emphasized the family’s wealth, influence, and devotion to tradition.

Comparison to Other Embalming Practices

The Caumont family’s embalming practices share similarities with those of the Medici family in Renaissance Italy. Both lineages used embalming to reinforce their social standing and ensure elaborate funeral rites. However, the Medici primarily focused on individual burials, whereas the Caumonts embalmed multiple family members, including children.

Another key distinction lies in the goals of embalming. In Egypt and South America, embalming aimed for long-term preservation, often driven by religious beliefs about the afterlife. In contrast, European embalming prioritized short-term preservation, facilitating public ceremonies and transportation of the deceased.

Cranial Clues: Analysis of Remains Unearthed in the Crypt

Legacy of the Château des Milandes

The Château des Milandes, built in the late 15th century by François de Caumont, has a rich and varied history. Originally a symbol of aristocratic grandeur, it later gained fame as the residence of American entertainer and civil rights activist Josephine Baker from 1947 to 1968. Today, the Château stands as a testament to its storied past, captivating visitors with its architectural beauty and historical significance.

The discovery of familial embalming practices adds another layer to the Château’s legacy. It serves as a window into the cultural and social norms of early modern France, offering invaluable insights into the lives and traditions of the aristocracy.

Conclusion

The discovery of familial embalming at Château des Milandes marks a significant milestone in European archaeology. By uncovering the burial practices of the Caumont family, researchers have reshaped our understanding of early modern funerary traditions. This finding not only highlights the sophistication of European embalming techniques but also underscores the cultural and ceremonial importance of these practices. As a symbol of resilience and history, the Château des Milandes continues to connect us to the fascinating narratives of Europe’s past.