Nicole Wilson was still in school when she learned about the Ice Age mummy. Stunned by the mysterious ink on his body, the now-adult artist took drastic measures to explore our history.

Nicole WilsonNicole Wilson at Three Kings Tattoo in Brooklyn, New York.

When Ötzi the Iceman was unearthed in 1991, his frozen 5,300-year-old body became the oldest preserved human ever found. Nicole Wilson was still a schoolgirl when she learned about the 61 tattoos discovered on his body. Now an artist, she has decided to get them replicated on herself — using her own blood as the ink.

According to Art Net, the Ice Age mummy was named after the Ötzal Alps on the Italian-Austrian border where it was found. The body was so intact that experts were able to identify his last meal and that he died of an arrow to the shoulder. Wilson, however, was most captivated by the ancient and mysterious tattoo art.

Comprised of lines and crosses, the tattoos were found in 16 groupings near Ötzi’s ribcage and lumbar spine, his wrist, knee, calves, and ankles. While these were made by rubbing pulverized charcoal into tiny cuts, Wilson used her own blood as ink — then photographed the tattoos being reabsorbed into herb body over four years.

According to Ancient Origins, she was so drawn to the idea of compressing time across the ages that she found the years-long process a perfect a complement. Now on display at a tattoo parlor in Brooklyn, her work aims to explore how much of our human history gets lost forever — and our duty to revisit those gaps.

South Tyrol Museum of ArchaeologyThe mummified corpse is on display at the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology.

On Sept. 19, 1991, hikers Helmut and Erika Simon stumbled upon Ötzi the Iceman’s corpse. It was so intact that they initially thought this was a fellow climber who recently died. Transported to the medical examiner’s office in Innsbruck a few days later, the “climber” was ultimately dated to between 3350 and 3100 B.C.

“I like to say he was preserved due to cataclysmic circumstances — a perfect storm of him dying as a storm came through, covering him in snow and ice that perfectly preserved his body,” said Wilson. “He’s a mummy, but not in the same way as Egyptian mummies. He wasn’t prepared for death in any way.”

Ötzi was indeed a so-called “wet” mummy: perfectly preserved by glacial ice on the exterior and the humidity of the ice keeping his organs and skin intact. Pollens found in his stomach confirmed he died in the spring or summer. Wilson said she was immediately fascinated by the mummy’s ink.

“The tattoos themselves are super interesting. Scientists think they might have acupuncture significance, but we don’t actually know,” said Wilson. “We can’t ask what the lines and the dashes and hashes meant to this person.”

Nicole WilsonWilson has lived with these tattoos for nearly a decade across two separate timeframes.

Now 33 years old, Wilson began the avant-garde project in 2012 and had a friend with a tattoo gun help her replicate the body art in her blood. Wilson essentially wanted to document the ancient mummy’s markings being absorbed into her body, with the heme (or pigment within blood) leaving dark scars even after fading.

“I started to become really obsessed with this idea of matching myself to history,” said Wilson. “If I could be a proxy for his body, or vice versa, what would that mean? It’s about closing some kind of historical time warp, as if we could compress time.”

“It’s interesting to live with marks on your body. You look down when you’re getting dressed, and are reminded of what you did and that connection that you’re trying to make. For years, I was thinking a lot about who I am and my relationship with history. It was a little sad for them to disappear completely.”

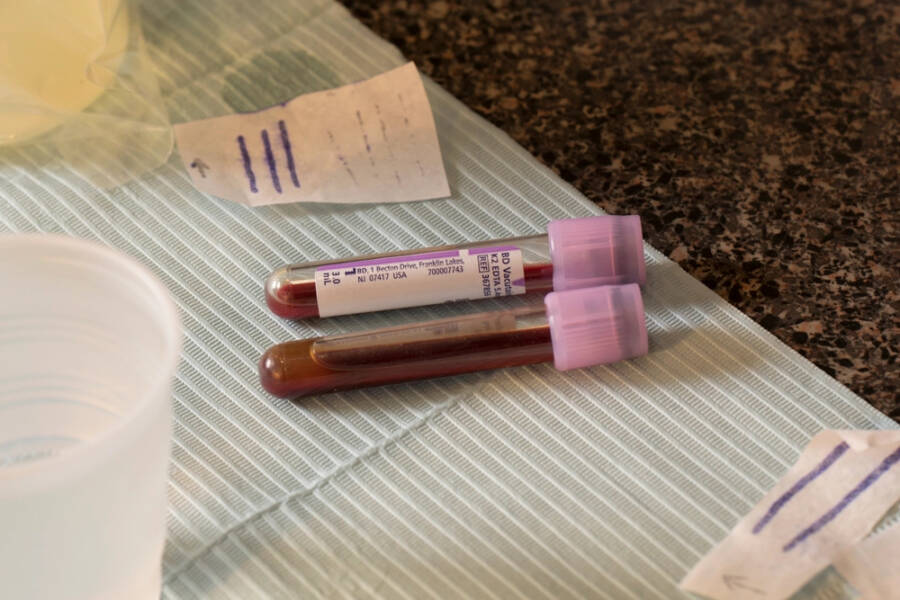

In 2015, researchers using multispectral imaging found two more tattoos on Ötzi’s mummified corpse. Ever the perfectionist, Wilson was thus eager to repeat her project in 2016 with the help of Three Kings Tattoo. The business agreed to both use her blood as ink and to showcase her photos at their Brooklyn location.

Nicole WilsonThe “ink” Wilson provided Three Kings Tattoo with.

“As empowering as the initial action may be, I cannot keep his marks; they slowly disappear over time and leave me,” said Wilson. “But, this poetic action simply mirrors that the connection between any two bodies are beholden to the laws of the universe and circumstantial limitation.”

The purpose of Ötzi the Iceman’s tattoos ultimately remains unclear. If the acupuncture theory is correct, his body bears the earliest known evidence of the practice and predates the first examples in Asia by 2,000 years. Ultimately, the unknowability and intangibility of history is precisely what Wilson wanted to explore.

“I’m trying to speak with the gaps in what we know and who we are,” she said. “So much of history ties itself up so neatly, but we need to talk about what’s missing and what gets left out — the gaps in history that are also making our contemporary stories today.”

For those who missed her work in New York, the “Nicole Wilson: Ötzi” exhibit will travel to Los Angeles and London in 2022. Her photographs will naturally be on display, but can also be digitally purchased in blockchain-authenticated individual groupings from $400 to $1,800 — or in a complete set for $10,000.