New details of rituals paint a picture that’s even more macabre than initially thought when this ancient human sacrifice site was first uncovered.

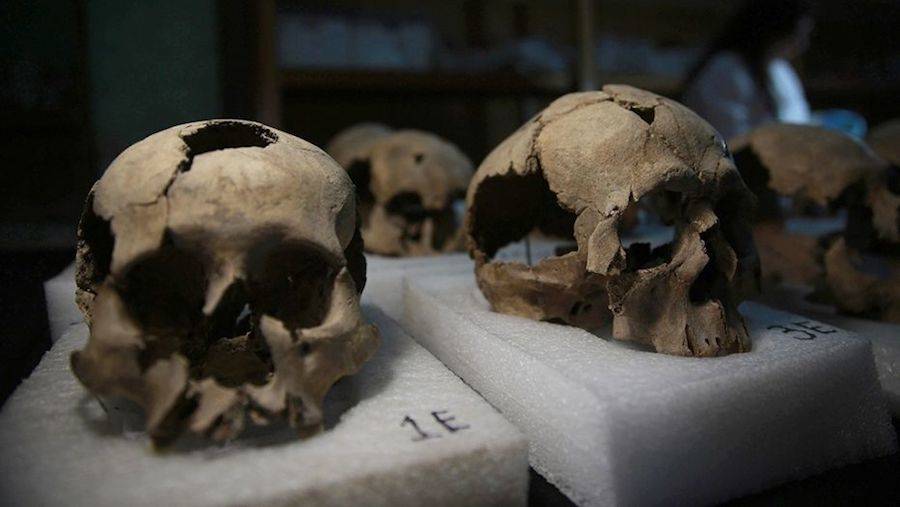

Daniel Cardenas/Anadolu AgencyUncovered skulls from the Aztec site.

In 2015, archeologists from Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History uncovered a tower of human skulls under an excavated Aztec temple in Mexico City. The skull tower – described circular tower built out of rings of human heads held together by lime, was made up of more than 650 skulls and thousands of fragments.

Well, experts have since been analyzing the details of the incredible discovery and the new revelations show just how horrific the nature of these sacrifices truly was.

The site was used for religious rituals where human sacrifices to honor the gods took place. Science magazine reported that the priests who performed the rituals sliced into the torsos and removed the still-beating hearts of those being sacrificed. The victims were then decapitated. Researchers said that the decapitation marks were “clean and uniform.”

Cut marks indicate that the priests “defleshed” the heads to mere skulls by removing the skin and muscle using sharp blades. Then they would carve large holes into the sides of the skulls so they could be slipped onto a large wooden pole, to be placed on an enormous rack at the front of the temple called the tzompantli.

The macabre process, which flourished between the 14th and the 16th centuries, has also been described in paintings and written descriptions from early colonial times.

Given the massive size of the tower and the tzompantli, experts have said that they believe several thousand skulls were likely displayed at one time.

Of the skulls and fragments found, archaeologists collected 180 mostly complete skulls from the tower. Some of the skulls were decorated and transformed into eerie masks.

ScienceDecorated skull mask.

One of the anthropologists studying the site, Jorge Gomez Valdes, found that of the skulls examined so far, most belonged to men (75 percent) between the ages of 20 and 35, which was considered “prime warrior age.” Women made up 20 percent of the victims and children made up five percent. It was determined that most were in relatively good health at the time of their deaths.

“If they are war captives, they aren’t randomly grabbing the stragglers,” said Gomez Valdes.

The mixed ages and genders support the theory that many victims were slaves sold specifically for the purpose of sacrifice.

The researchers said that samples have already been taken from many of the skulls for DNA testing and, in addition to the age and sex diversity, they expect to find diverse origins as well. The belief comes from the fact that the skulls had various dental and cranial modifications that were practiced by different cultural groups.

“Hypothetically, in this tzompantli, you have a sample of the population from all over Mesoamerica,” said Lorena Vazquez Vallin, another one of the researchers. “It’s unparalleled.”

By continuing to study the details of the remains, the researchers hope to learn more about the peoples’ rituals, where they came from, and what their personal stories were.