A new research paper claims to reveal new facts about the ancient Persian (Achaemenid) Empire. While headlines tell of the 33 Achaemenid clay tablets determining that Persian laborers were paid wages in silver coins, in 1970 Dr. Paul Naster had already concluded that “Achaemenid laborers were paid with silver coins.” So, although a glimpse into a fascinating era and ancient civilization, is this really news?

The Achaemenid (aka Persian) Empire was founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC with the building of the city of Takht-e Jamshid, or Persepolis, which went on to become the ceremonial and administrative capital of the Persian Empire. With its immense terrace and maze of palaces and royal residences at Persepolis, the Achaemenid empire stretched from Ethiopia across Egypt, to Greece and modern Turkey, down to India, and all the way over to Central Asia, and it lasted until 330 BC.

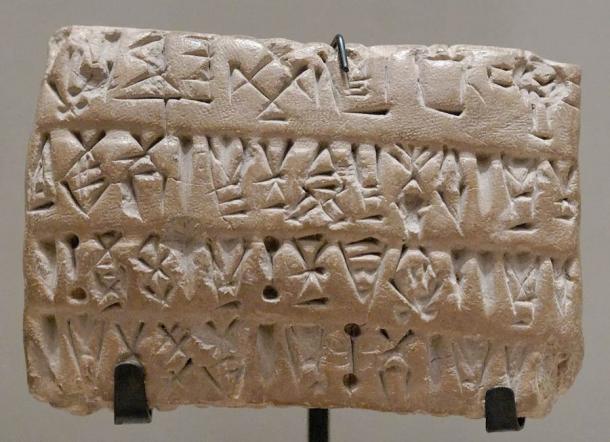

Economic tablet with numeric signs and Proto-Elamite script. (Louvre Museum / CC BY 2.5)

Social Secrets of Darian Clay Tablets

Iranian archaeologist, Dr. Soheli Delshad, has published his recent investigation of 33 Achaemenid clay tablets. He told Tehran Times that the ancient texts tell of the economic, social and religious history of the Achaemenid Empire. Each of the 33 tablets in this study were inscribed with Elamite Cuneiform and were created during the reign of Darius I (Darius the Great), the third Persian King of Kings, who ruled between 522 BC and 486 BC.

In an ILNA report released last Wednesday, Dr. Delshad explained that “4 of the tablets came from a fort archive” and that “28 were selected from the royal treasury of Persepolis.” I’ll let you do the math on that one. The conclusion of the new study was, however, that all of the 136 workers mentioned in the tablets “were paid in silver from the king’s treasury.” But you will soon have to ask yourself, is this really news?

Ink painting of Darius I by Gustave Moreau. The clay tablets were supposedly created during his reign. (Public domain)

Whispers from One of the Largest Ancient Centers of Power

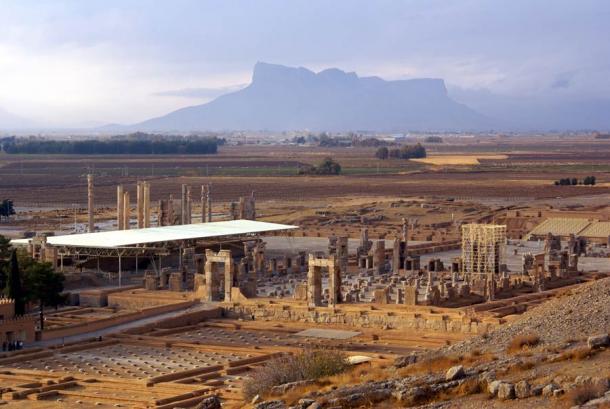

The source of most of the tablets was ancient Persepolis, which is located about 60 kilometers (37 mi) northeast of the Iranian city of Shiraz, in Fars province, at the base of Kuh-e Rahmat (Mountain of Mercy). This ancient cultural center, which was legendary for its city planning, architecture, arts and technologies, was torched by Alexander the Great in 330 BC in response to the Persian King Xerxes’ burning of the Greek city of Athens about century and a half earlier.

Persepolis became a sprawling 13-ha (32 acres) “mega-seat” of the Achaemenid government, that represents one of the most expansive archaeological sites in the world. While King Cyrus famously founded the city, a string of later kings commissioned their architects to restore and completely rebuild several huge palaces, including the Apadana Palace and Apadana Throne Hall, also known as the Hundred-Column Hall.

General view of the ancient city of Persepolis, where most of the clay tablets were originally found. (Valery Shanin / Adobe Stock)

Untwisting the Controversial Clay Tablets

The clay tablets were originally discovered in the 1930s by archaeologists from the University of Chicago. Since 1935, they have been on loan to the United States and were kept in the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. However, in February 2018 the United States Supreme Court instructed that the tablets, and other ancient Persian artifacts, should be returned to Iran.

Thus, in 2019, hundreds of Achaemenid clay tablets were repatriated and made their way home. Gil Stein, director of the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago, told Tehran Times that this new study results from a collaborative project with university researchers in Iranian institutes. However, why no mention of the intrepid Dr. Naster, who you will now see nailed all this down over 50 years ago.

Where is the News Here?

While researching for this article, I came upon the journal Ancient Society. Founded in 1970 by the Ancient History section of the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, this research group studied Greek, Hellenistic and Roman societies. In that same year, Dr. Paul Naster published a paper whose title asked the question “Were the laborers of ancient Persepolis paid in money?”

Naster’s 1970s paper concluded that King Darius “struck coins, in silver about the year 515 AD.” Furthermore, he went so far as to say the workers were initially paid with “silver lumps, and later cast silver coins.” Today’s Tehran Times headline reads “Achaemenid workers paid silver for wages,” and unless I am missing something, isn’t this close to exactly the same headline and conclusion? Although this offers a chance to talk about a key place in world history, is there anything new about this latest Achaemenid clay tablet announcement? Are they really telling us anything we didn’t know already