300,000 years ago, the Earth was home to at least nine human species, each navigating their environment with unique adaptations. Today, only Homo sapiens remain. This raises a profound question: why did our species survive while others vanished? New research reveals a fascinating combination of biological, environmental, and social factors that secured our place as the last human species on Earth.

The Rise of Homo Sapiens

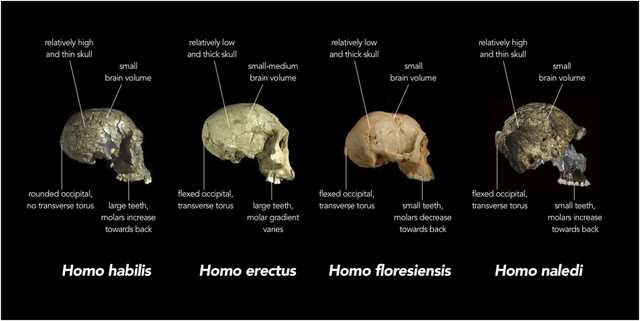

Homo sapiens emerged around 300,000 years ago in Africa, evolving unique features like round skulls, vertical foreheads, and chins, which set them apart from other Homo species. Unlike Neanderthals with their robust frames or Homo naledi with smaller brains, early H. sapiens showcased an unmatched adaptability. Recent discoveries, including fossils from Morocco, Ethiopia, and South Africa, suggest our species did not originate from one specific region but evolved across multiple sites, challenging previous assumptions of a single “cradle of humanity.”

Further evidence for the ‘out of Africa’ model can be found in the size of human skulls

From about 80,000 years ago, H. sapiens began spreading out of Africa, encountering and sometimes interbreeding with other human species. Genetic evidence points to complex interactions, hinting at both cooperation and competition.

Delving Into a Lost World of Other Human Species That Once Walked the Earth Alongside Our Ancestors

Competition with Other Homo Species

By the time H. sapiens expanded into Europe and Asia, they encountered a world already populated by diverse human species. Neanderthals roamed Europe, thriving in colder climates. The Denisovans occupied parts of Asia, leaving their genetic imprint in populations from Oceania. Smaller, island-adapted species like Homo floresiensis, nicknamed the “Hobbit,” and H. luzonensis lived in Indonesia and the Philippines, while Homo erectus and Homo naledi persisted in pockets elsewhere.

However, these species were not as widespread as H. sapiens. Sparse fossil evidence, such as isolated finds of H. naledi in South Africa or Denisovan remains in Siberia, suggests smaller populations. Genetic studies reveal that these species often lived in small, isolated groups, making them more vulnerable to environmental shifts and disease. In contrast, H. sapiens formed larger, more interconnected social networks, which proved to be a key survival advantage.

A Comparative View of Three Skulls: A Neanderthal on the Left, a Modern Human in the Center, and Australopithecus afarensis on the Right, Showcasing the Evolutionary Diversity of Early Humans.

Hypotheses for the Survival of Homo Sapiens

Biological Edge

Larger brains enabled H. sapiens to solve problems, innovate tools, and adapt to new environments. Unlike other Homo species, they demonstrated a knack for creating specialized tools for hunting, building, and clothing. These innovations improved survival rates in diverse climates.

Social Networks

H. sapiens had expansive social networks, often forming alliances with distant kin. This cooperation extended to sharing resources and innovations. When faced with crises like droughts or food shortages, such networks provided a safety net, enabling survival in challenging environments.

Environmental Resilience

Research shows that later Homo species, especially H. sapiens, could adapt to a broader range of ecosystems. During Ice Ages and environmental changes, H. sapiens’ ability to migrate and settle in new areas ensured survival where others struggled.

Technological Innovation

The invention of sewing needles and insulated clothing allowed H. sapiens to survive in colder climates, while advances in weaponry enhanced hunting efficiency. Such small but significant innovations likely gave them a competitive edge over species like Neanderthals.

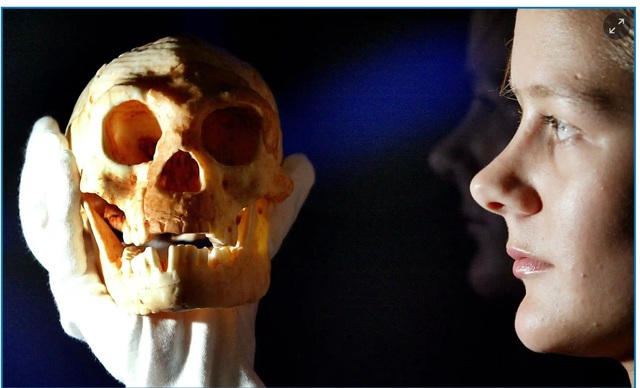

A Replica of the Skull of Homo floresiensis, Unearthed on Indonesia’s Island of Flores, Highlights a Unique Branch of the Human Family Tree

The Role of Interbreeding

Homo sapiens didn’t entirely replace other species. Genetic studies reveal that interbreeding occurred with Neanderthals and Denisovans, leaving traces of their DNA in modern humans. For example, many people of European descent carry up to 2% Neanderthal DNA, while populations in Oceania have up to 4% Denisovan DNA.

This genetic mixing likely played a role in the disappearance of these species. However, whether interbreeding was a factor in their extinction or simply a byproduct of coexistence remains debated. Some researchers argue that hybrid offspring may have diluted the distinct genetic identity of these species over generations, while others suggest their extinction stemmed from broader environmental pressures.

The Luck Factor

Survival often comes down to chance. Small populations, like those of Neanderthals and Denisovans, were more susceptible to extinction from sudden disasters, diseases, or resource scarcity. In contrast, H. sapiens benefited from larger, more genetically diverse groups, which provided greater resilience.

Interestingly, even H. sapiens faced moments of near-extinction. Genetic studies suggest that around 800,000 years ago, our ancestors experienced a population bottleneck, with numbers dropping to just a few thousand individuals. Their survival, and eventual dominance, may owe as much to luck as to their adaptability.

Conclusion

The survival of Homo sapiens over other human species was not due to a single factor but a combination of biology, environment, social structures, and chance. Our larger brains, cooperative networks, and adaptability to changing climates gave us an edge, while interbreeding and sheer luck played their parts. Today, the story of our ancestors reminds us of the importance of resilience and collaboration in the face of challenges. As we confront global issues, from climate change to social inequality, these lessons from our past remain profoundly relevant.