In 1881, the ancient city of Sippar, located along the banks of the Euphrates River in modern-day Iraq, revealed one of the most extraordinary archaeological finds: a clay tablet now recognized as the world’s oldest known map. Discovered by Iraqi Assyriologist Hormuzd Rassam during an excavation for the British Museum, this clay artifact offers a fascinating look into the Babylonian world view from over 2,500 years ago. Today, we know this artifact as the “Babylonian Map of the World” or “Imago Mundi.” It blends elements of geography, mythology, and spiritual belief, presenting a unique perspective of how the Babylonians perceived their world.

Discovery of the Babylonian Map of the World

The Babylonian Map of the World, unearthed by Rassam during his 1881 excavation near Sippar, initially did not receive much attention from researchers. However, upon closer examination, this small, delicate tablet—measuring only 12.2 by 8.2 centimeters—revealed itself to be a critical window into the past. Dated between 700 and 500 BCE, the map is now housed in the British Museum, where it continues to intrigue scholars and visitors alike.

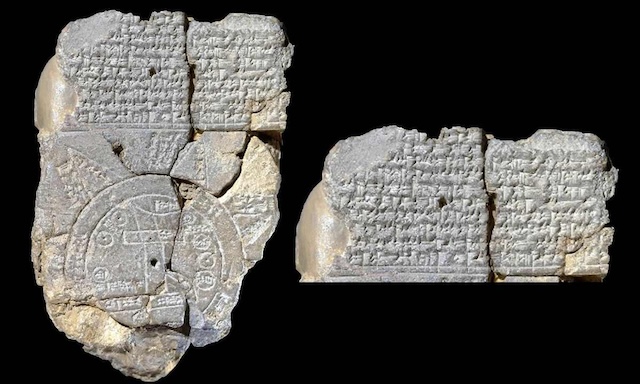

The clay tablet features intricate carvings and inscriptions that depict the Babylonian understanding of the world. At the heart of this depiction lies Babylon, encircled by regions such as Assyria and Elam, which were significant territories in the ancient Babylonian empire. Surrounding these regions is a circular waterway labeled as the “Salt Sea” or “Bitter Water,” symbolizing the boundaries of the known world. Beyond this waterway lies the mysterious and unknown, illustrating both the geographical and cosmological beliefs of the time.

Close-up of the ancient clay tablet known as the Babylonian Map of the World, highlighting Babylon’s central position.

A Unique Depiction of the World

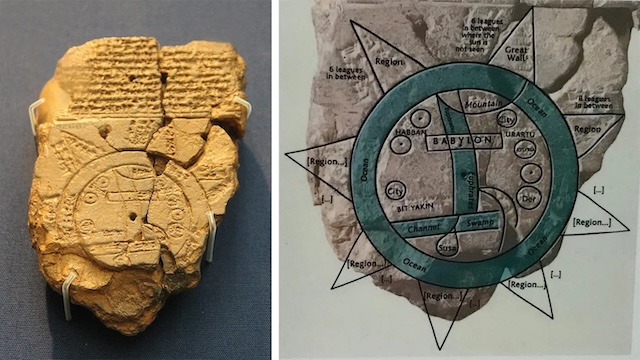

The map, though small in size, holds a wealth of information. Unlike modern maps, which aim for geographical accuracy and scale, the Babylonian Map of the World provides a symbolic portrayal of the world as the Babylonians knew it. Babylon, at the center, is depicted as the heart of civilization. The Euphrates River is represented as two lines running vertically through the disk, indicating its flow from the northern to the southern regions.

Above Babylon, the map features a gap marked as “mountain,” believed to represent the Zagros Mountains. This demonstrates the Babylonians’ understanding of their geographical surroundings. Other marked regions, such as Assyria and Elam, showcase the political and cultural significance these areas held within the empire.

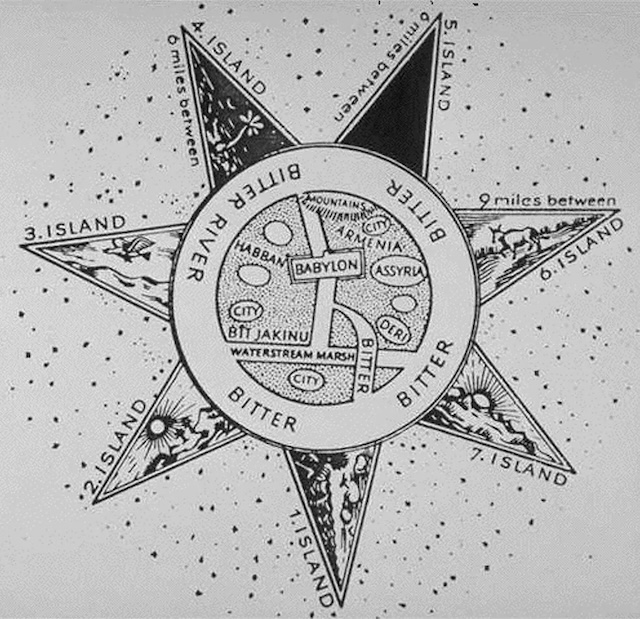

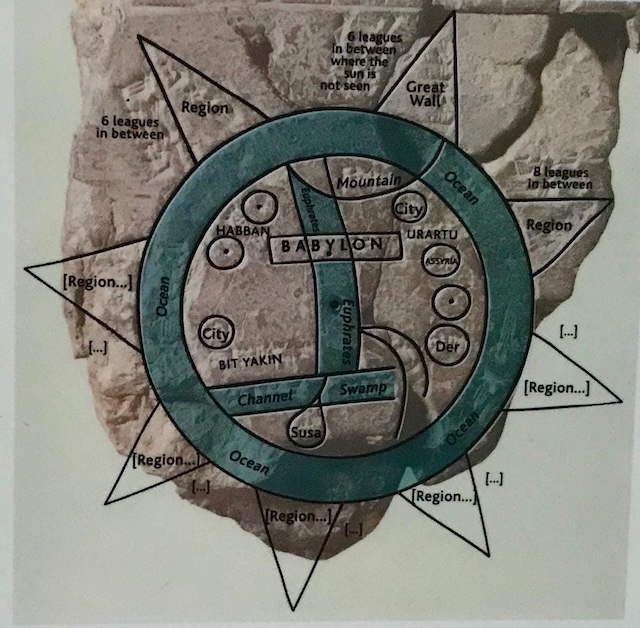

Interestingly, the map includes triangular shapes beyond the encircling “Bitter Water,” which symbolize distant lands or islands. Each triangle is marked with specific distances, reflecting the Babylonians’ efforts to chart regions that were shrouded in mystery and myth. This combination of geographical knowledge and mythical representation makes the map an invaluable artifact for understanding the ancient world.

A diagrammatic reconstruction of the Babylonian Map of the World, illustrating key geographical and mythical regions.

Gods, Monsters, and Legendary Kings

The Babylonian Map of the World is more than just a geographic representation; it also encompasses aspects of mythology and legend. Above the map, inscriptions reference Marduk, the patron god of Babylon. In Babylonian mythology, Marduk was a powerful deity who battled various creatures, both natural and supernatural. These inscriptions also mention legendary kings, such as Utnapishtim and Nur-Dagan, alongside the historical figure Sargon, the king of Akkad.

The presence of these gods, mythical creatures, and legendary rulers suggests that the Babylonians viewed their world as one deeply intertwined with the divine and the supernatural. The regions beyond the “Bitter Water” were not just distant lands but places inhabited by legendary beings, indicating that the Babylonians saw the physical world and the spiritual realm as interconnected.

Front and back views of the Babylonian clay tablet, inscribed with cuneiform text and the world map.

Blending Geography and Mythology in the Oldest Map of the World

One of the most captivating aspects of this ancient map is its blend of geographical and mythical elements. The map does not merely outline territories; it also incorporates spiritual and cultural beliefs. The cuneiform inscriptions speak of strange creatures and mythical heroes, residing in lands far beyond the known regions.

This blending of physical geography with mythology demonstrates the Babylonians’ worldview. For them, the world was not just a collection of lands and seas but a cosmos where the physical and spiritual realms coexisted. The triangular regions beyond the “Bitter Water” are symbolic of this belief, suggesting that the Babylonians sought to understand both the known and the unknown in holistic terms.

Side-by-side comparison of the original Babylonian Map and its modern interpretation, depicting regions, waterways, and the surrounding “Bitter Water.”

The Oldest Map’s Historical Significance

The Babylonian Map of the World is a significant artifact, not just for its geographical details but also for its cultural and religious implications. By placing Babylon at the center of the map, the Babylonians were making a statement about their city’s cultural and spiritual importance. This central positioning reflected their belief that Babylon was the hub of civilization and power.

The “Bitter Water” encircling the known world aligns with the ancient belief that a vast ocean surrounded the earth, a concept found in various other cultures, including ancient Greek and Hindu cosmologies. However, the Babylonian map stands out for its symbolic representation of these ideas, prioritizing the spiritual and mythological significance of places over geographical precision.

A closer view of the annotated Babylonian Map of the World, marking various regions, mountains, and cities encircled by the “Bitter Ocean.”

Legacy of the Oldest Map of the World

The Babylonian Map of the World has left an indelible mark on the history of cartography. While modern maps prioritize scientific accuracy, the influence of this ancient map is still evident in how we conceptualize geography in cultural and mythological contexts. This artifact serves as a reminder that maps are not just tools for navigation but also reflections of cultural beliefs and worldviews.

Current research by the University of Vienna, in collaboration with the British Museum, seeks to delve deeper into ancient Mesopotamian maps, including this one. Using advanced imaging techniques and comparative analysis, scholars like Prof. Robert Rollinger and Dr. Silvia Kutscher aim to uncover more about how the Babylonians and other ancient cultures perceived and charted their worlds.

Conclusion

The discovery of the Babylonian Map of the World near Sippar remains one of the most remarkable finds in the field of archaeology. This small clay tablet provides a unique glimpse into how the Babylonians viewed their world over 2,500 years ago. By blending geography, mythology, and spirituality, the map illustrates a cosmology where the known and the unknown are interconnected, with Babylon at the center of existence. Its legacy continues to influence modern understandings of early cartography, highlighting that maps are not merely geographical tools but also cultural artifacts that reveal how ancient peoples understood their world and their place within it.