Archaeology is always full of surprises. When an excavation is started, the team never knows what the next artifact will be to see the light of day. Many times a find is mundane – pottery shards, inconclusive artifacts, and ancient garbage. But there are rare occasions when the dig proves to be an excavation of a lifetime and is certain to make the headlines. Such is the story of this unbelievable archaeological dig from China, when a stunning 10 tons of ancient coins were unearthed in a single burial chamber. There’s no doubt that the history of ancient China was filled with wonders and extravagance, but this discovery really put the benchmark way up high. It was Liu He’s tomb filled with two million coins and other luxury items.

An Afterlife of Wealth: The Discovery of Liu He’s Tomb of 2 Million Coins

In the Xinjian district of Nanchang, in China’s eastern Jiangxi Province, archaeologists have discovered one of the most important discoveries of our time, and certainly one of China’s unprecedented finds. The discovery was made unexpectedly. Hearing reports of some minor grave robbing in the Xinjian district, the president of the Institute of Cultural Heritage and Archaeology of Jiangxi Province, Mr. Xu Changqing, quickly got in touch with Yang Jun and the Jiangxi Institute of Archaeology.

On March 24, 2011, the team visited the reported “hole” and made the discovery of their lives. A sprawling tomb complex was gradually unearthed, and the magnitude of the site was quickly confirmed. It would take years to fully unearth this set of tombs, which are set on 3700 square meters (40,000 square feet) and have walls that measure up to 900 meters (almost 3000 feet).

Even though the team quickly concluded that a part of the tombs had already been looted sometime in ancient history, roughly around the period of the Five Dynasties of China (907-960 AD), the amount of excavated treasures was astonishing. The level of preservation and the number of finds all have to do with the complexity of the tomb complex – the tomb is akin to an underground “city,” with numerous chambers connected with corridors and sloping pathways.

The remarkable site yielded some of the finest archaeological discoveries in modern history, and certainly in China. It is considered the best-preserved royal tomb from the Han Dynasty period, and the one with the most important finds. The amount of discoveries was mind-boggling, and certainly provided an important glimpse into the royal funerary practices of ancient China, as well into the wealth of its nobility.

Gold, copper, jade, amber, and bronze items have been unearthed – more than 20,000 of them. And each item is extravagantly made – the finest craftsmanship, incredible details, and immense wealth are obvious from even a glance. The complexity and the extravagance are in fact so complex, that they are advanced even by today’s standards. From elaborate gold pendants, figures, and decorative items, to jade items and bronze vessels, to swords and mirrors, stunning amber figurines, bronze bells and terracotta soldiers, royal seals and writings, and chessboards and kitchenware – the number of artifacts was unbelievable.

Some especially important finds were discovered here as well. One example is a large bronze mirror with an intricate painting on its back displaying Confucius, the renowned philosopher. Known thereafter as the “Confucius Dressing Mirror,” it is the earliest known surviving portrait of the ancient Chinese philosopher.

Back side of the Confucius Dressing Mirror. Earliest surviving portrait of Confucius (top left). First Century, B.C. Tomb of the Marquis of Haihun, Jiangxi Province. (Ziliang Liu)

“You Can’t Take it to the Grave”

The other groundbreaking discovery is the lost Qi Lun version of the Analects of Confucius (Selected Sayings). The analects were formed into three distinct versions in antiquity – the Lu Lun, Gu Lun, and Qi Lun. The latter was presumed to be lost for 1800 years, until it was discovered in this very tomb at Xinjian. Like most writings of that period, the Qi Lun was written on thin bamboo strips – around 5000 of them – and its re-discovery is a milestone in modern archaeology.

Another crucial discovery was a horse and chariot burial. The ancient Chinese of the Han Dynasty had strict regulations about these types of burials, and this one was the first of this kind to be discovered south of the Yangtze River. The burial pit contained the remains of five extravagant wooden chariots, and the skeletons of 20 horses, all accompanied with some 3000 pieces of extremely elaborate bronze and gold riding gear and chariot decorations.

Gold horseshoe decorations from the Liu He tomb. (Image: nocoev.com)

Combined with all the rest of the findings – more than 500 pieces of exquisite jade ware, 5000 pieces of gold (over 150 kilograms or 330.69 lb. of it), silver, and bronze, 500 pieces of ceramics, and 3000 of wooden lacquer ware – the site at Xinjian eclipses all other archaeological discoveries from the Han Dynasty in China.

But the most interesting discovery is certainly unique in any part of the world. In the northern section of the tomb, the archaeologists discovered a stunning find – some 2 million wu zhu bronze coins. They have the combined weight of over 10 tons, and are worth around 50 kilograms (110.23 lbs.) of gold today. The coins were all piled up, making a two meter (6.56 ft.) high mound.

Originally they were piled up on strings or sticks, one thousand per string. The wu zhu coins, as the majority of coins throughout most of ancient Chinese history, had a circular shape and a square hole in the center. This hole was created so the coins could be strung and thus transported and counted more easily.

A beastly deity in jade (CC BY SA 4.0) and gold ingots (CC BY SA 4.0) found in the tomb of the Marquis of Haihun and ex Han Dynasty Emperor, Liu He.

It is speculated that the 2 million coins would have been highly valued in their time – equivalent to a million US dollars. The coins are singlehandedly the largest discovery of their type in our time, and are remarkably preserved, with some of them even having the remaining sticks, and the original “strung” layout. The ancient Chinese interred their noble dead with all the goods needed in afterlife – and judging from such wealth and so many coins, the deceased had big plans for after his death.

Becoming the Marquis Haihun

It was soon confirmed that the tomb complex at Xinjian belonged to the well-known historical figure from the period of the Han Dynasty (~202 BC – 220 AD) – the Marquis of Haihun, Liu He. Haihun was an ancient county that corresponds to the location of the modern Xinjian.

Liu He (劉賀) (c. 92-52 BC), was one of the unique characters of the history of the Han Dynasty and ancient China. A grandson of Liu Che, the Emperor Wu of Han, the seventh and longest ruling Emperor of Han Dynasty, and his favored concubine Li Furen, Liu He inherited the title King of Changyi. It is possible that he inherited this title at only six years of age. In the ancient writings Liu He is generally portrayed as an unruly and vulgar young prince (or King), with a knack for wasting his wealth and living a high life.

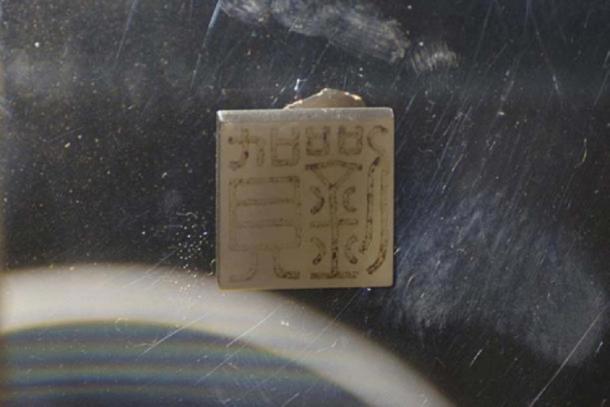

Personal stamp of Liu He. (Siyuwj/CC BY SA 4.0)

Upon the death of his uncle, the Emperor Zhao of Han, and the unclear succession, it was Liu He that was in line for the throne, being a grandson to the previous emperor. Possibly installed as a puppet by the powerful politician and official Huo Gang, Liu He immediately accepted the throne and raced off to the capital – Chang’an.

But it was soon obvious to Huo Gang that he made a mistake in choosing young Liu He for the throne. The new emperor was simply too vulgar and unruly – he disregarded all pleas for humility and moderation. Instead, he chose to overlook the traditional mourning of the nation for the dead Emperor, and went on with his wasteful ways, drinking, feasting, and enjoying women. He gave promotions to whomever he pleased. All of his actions quickly made him unpopular with Huo Gang and all other important officials, who agreed to remove him from the throne.

After only 27 days of rule, the officials presented the articles needed for the impeachment of Liu He. The list consisted of an amazing 1127 individual examples of misconduct, including: engaging in feasts and games in a time of mourning, refusing to abstain from sex and meat during the mourning period, failing to keep the palace secure, improperly promoting his subordinates, and so on.

The impeachment was approved, and Emperor Liu He was deposed of his titles and ordered to return to his previous province, Changyi. He was no longer the King of that province; in fact he had no titles anymore, but he was still allowed a small holding with 2,000 families paying him taxes.

But later on, 10 years after his was deposed as the short lived emperor, Liu He was once more upgraded to a title, ending his “exile” commoner status. In 63 BC he was proclaimed a Marquis of Haihun, becoming the first of the four generations of Haihun Marquises.

Badge of the Marquis of Haihun. (Image: nocoev.com)

The Spectacular Tomb of Liu He

Liu He died in 59 BC at just 33 years old, and was eventually succeeded by his eldest son Liu Daizong (劉代宗), the Second Marquis Haihun.

And it is for Liu He that this sprawling and luxurious tomb was constructed. It also held the remains of his son Liu Chongguo (劉充國) and his consort. From the sheer wealth of this tomb, and the amount of riches unearthed, it is clear that Liu He, although he was an emperor for only 27 days, still managed to retain much of his wealth, even after losing both his Kingship of Changyi and his Emperor’s title. And after becoming a marquis, he once more established his wealth.

But these rich finds, and the groundbreaking discoveries in the tomb also tell us that Liu He was not as insignificant as his contemporaries presented him. It is clear that Liu He was the most prominent and wealthy local aristocrat during the Han Dynasty, and he was continually feared by the new Emperor Xuan.

The tomb discovery itself is of great importance for Chinese scientists and researchers as it provides a crucial insight into ancient Chinese and Han Dynasty society, funerary practices, and afterlife beliefs. The discoveries of the Qi Lun version of Analects of Confucius, as well as the painting of that philosopher and many of his followers, confirms the policy of the Western Han dynasty which states that it would “be solely venerating Confucianism.”

Besides the Qi Lun discovery, which was carefully written on 5000 bamboo strips, many other wooden tablets and inscriptions were discovered, providing a glimpse into the period. These bamboo strips, although diminished by time, moisture, and mud, and discovered clumped and bunched up into a gooey mass, were painstakingly separated, catalogued, and preserved. With the help of infrared lighting, the inscriptions were made clear and quite easy to read. Still, the process of documenting all the inscriptions will take approximately five more years.

Wealth Beyond Measure

In the history of China, the Han Dynasty is considered a golden age. And in that period, Liu He was the Emperor with the shortest reign. History seemingly passed him by, but there is no doubt now that Liu He was more than a fun loving, vulgar, and extravagant noble with a knack for spending his wealth.

His wealth and influence were important, and are at last evidenced by the sheer amount of riches with which he was entombed. And time was kind to his tomb – it is one of the finely preserved ancient Chinese tombs, and an archaeological site that’s the dream of every enthusiastic archaeologist – it’s full of finely-preserved wonders.

Goose-shaped bronze lamp excavated from the tomb of Marquis of Haihun. (Siyuwj /CC BY SA 4.0)

And ultimately, the tomb of Liu He paints an interesting parallel between the East and the West, showing us just how far ahead of their contemporaries the ancient Chinese were. In a time when Julius Caesar was steadily rising to the top, the Chinese were already experiencing their golden age, priding themselves on the sheer splendor of their aristocratic lives. And it goes to show us just how diverse the history of the world is, and the uniqueness of the ancient dynasties of China.