Nefertiti was the chief consort of the Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten (formerly Amenhotep IV), who reigned from approximately 1353 to 1336 BC. Known as the Ruler of the Nile and Daughter of Gods, Nefertiti acquired unprecedented power, and is believed to have held equal status to the pharaoh himself. However, much controversy lingers about Nefertiti after the twelfth regal year of Akhenaten, when her name vanishes from the pages of history.

In Akhenaten’s new state, religion centred on the sun god, he and Nefertiti were depicted as the primeval first couple. Nefertiti was also known throughout Egypt for her beauty. She was said to be proud of her long, swan-like neck and invented her own makeup using the Galena plant. She also shares her name with a type of elongated gold bead, called nefer, that she was often portrayed as wearing.

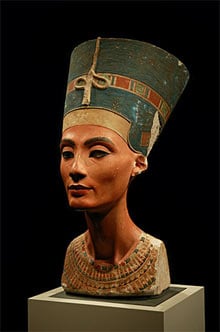

Long forgotten to history, Nefertiti was made famous when her bust was discovered in the ruins of an artist’s shop in Amarna in 1912, now in Berlin’s Altes Museum. The bust is one of the most copied works of ancient Egypt.

The iconic bust of Nefertiti, discovered by Ludwig Borchardt, is part of the Ägyptisches Museum Berlin collection, currently on display in the Altes Museum. Image Source: New World Encyclopedia

Nefertiti is depicted in images and statuary in a large image denoting her importance. Many images of her show simple family gatherings with her husband and daughters. She is also known as the mother-in-law and stepmother of the Pharaoh Tutankhamun.

Nefertiti’s parentage is not known with certainty, but it is generally believed that she was the daughter of Ay, later to be pharaoh after Tutankhamen. She had a younger sister, Moutnemendjet. Another theory identifies Nefertiti with the Mitanni princess Tadukhipa.

Nefertiti was married to Amenhotep IV around 1357 BC and was later promoted to be his queen. Images exist depicting Nefertiti and the king riding together in a chariot, kissing in public, and Nefertiti sitting on the king’s knee, leading scholars to conclude that the relationship was a genuine one. King Akhenaton’s legendary love is seen in the hieroglyphs at Amarna, and he even wrote a love poem to Nefertiti:

…And the Heiress, Great in the Palace, Fair of Face, Adorned with the Double Plumes, Mistress of Happiness, Endowed with Favors, at hearing whose voice the King rejoices, the Chief Wife of the King, his beloved, the Lady of the Two Lands, Neferneferuaten-Nefertiti, May she live for Ever and Always…

The couple had six known daughters, two of whom became queens of Egypt: Meritaten (believed to have served as her father’s queen), Meketaten, Ankhesenpaaten/Ankhesenamen (later queen to Tutankhamun), Neferneferuaten Tasherit, Neferneferure, and Setepenre.

A “house altar” depicting Akhenaten, Nefertiti and three of their daughters; limestone c. 1350 B.C.E., Ägyptisches Museum Berlin. Image source: New World Encyclopedia.

New Religion

In the fourth year of Amenhotep IV’s reign, the sun god Aten became the dominant national god. The king led a religious revolution closing the older temples and promoting Aten’s central role. Nefertiti had played a prominent role in the old religion, and this continued in the new system. She worshiped alongside her husband and held the unusual kingly position of priest of Aten. In the new, virtually monotheistic religion, the king and queen were viewed as “a primeval first pair,” through whom Aten provided his blessings. They thus formed a royal triad or trinity with Aten, through which Aten’s “light” was dispensed to the entire population.

During Akhenaten’s reign (and perhaps after) Nefertiti enjoyed unprecedented power, and by the twelfth year of his reign, there is evidence that she may have been elevated to the status of co-regent, equal in status to the pharaoh himself. She is often depicted on temple walls in the same size as him, signifying her importance, and is shown alone worshiping the god Aten.

The Wilbour Plaque, Brooklyn Museum. Nefertiti is shown nearly as large as her husband, indicating her importance. Image source: Brooklyn Museum

Perhaps most impressively, Nefertiti is shown on a relief from the temple at Amarna smiting a foreign enemy with a mace before Aten. Such depictions had traditionally been reserved for the pharaoh alone, and yet Nefertiti was depicted as such.

Akhenaten had the figure of Nefertiti carved onto the four corners of his granite sarcophagus, and it was she who is depicted as providing the protection to his mummy, a role traditionally played by the traditional female deities of Egypt: Isis, Nephthys, Selket and Neith.

Nefertiti’s Disappearance

In the regal year 12, Nefertiti’s name ceases to be found. Some think she either died from a plague that swept through the area or fell out of favour, but recent theories have denied this claim.

Shortly after her disappearance from the historical record, Akhenaten took on a co-regent with whom he shared the throne of Egypt. This has caused considerable speculation as to the identity of that person. One theory states that it was Nefertiti herself in a new guise as a female king, following the historical role of other women leaders such as Sobkneferu and Hatshepsut. Another theory introduces the idea of there being two co-regents, a male son, Smenkhkare, and Nefertiti under the name Neferneferuaten (translated as “The Aten is radiant of radiance [because] the beautiful one is come” or “Perfect One of the Aten’s Perfection”).

Some scholars are adamant about Nefertiti assuming the role of co-regent during or after the death of Akhenaten. Jacobus Van Dijk, responsible for the Amarna section of the Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, believes that Nefertiti indeed became co-regent with her husband, and that her role as queen consort was taken over by her eldest daughter, Meryetaten (Meritaten) with whom Akhenaten had several children. (The taboo against incest did not exist for the royal families of Egypt.) Also, it is Nefertiti’s four images that adorn Akhenaten’s sarcophagus, not the usual goddesses, which indicates her continued importance to the pharaoh up to his death and refutes the idea that she fell out of favour. It also shows her continued role as a deity, or semi-deity, with Akhenaten.

On the other hand, Cyril Aldred, author of Akhenaten: King of Egypt, states that a funerary shawabti found in Akhenaten’s tomb indicates that Nefertiti was simply a queen regnant, not a co-regent and that she died in the regal year 14 of Akhenaten’s reign, her daughter dying the year before.

Some theories hold that Nefertiti was still alive and held influence on the younger royals who married in their teens. Nefertiti would have prepared for her death and for the succession of her daughter, Ankhesenpaaten, now named Ankhsenamun, and her stepson and now son-in-law, Tutankhamun. This theory has Neferneferuaten dying after two years of kingship and being then succeeded by Tutankhamun, thought to have been a son of Akhenaten. The new royal couple was young and inexperienced, by any estimation of their age. In this theory, Nefertiti’s own life would have ended by Year 3 of Tutankhaten’s reign. In that year, Tutankhaten changed his name to Tutankhamun and abandoned Amarna to return the capital to Thebes, as evidence of his return to the official worship of Amun.

A gold plate found in Tutankhamun’s tomb depicting Tutankhamun and Ankhesenamen together

As the records are incomplete, it may be that future findings of both archaeologists and historians will develop new theories vis-à-vis Nefertiti and her precipitous exit from the public stage. To date, the mummy of Nefertiti, the famous and iconic Egyptian queen, has never been conclusively found.