Researchers traced the man’s ancestry to Sardinia and present-day Turkey — and found that he likely suffered from spinal tuberculosis.

Notizie Degli Scavi di AntichitaThe man in question was first discovered in 1933. Nearly one century later, his human genome has been sequenced.

When Mount Vesuvius erupted in 79 A.D., the 20,000 residents of Pompeii who stood in its shadow were either buried under 23 feet of ash and debris or fled. That layer kept many of the Pompeii victims’ remains intact to this day, and for the first time ever, scientists have now sequenced the genome of one of the victims.

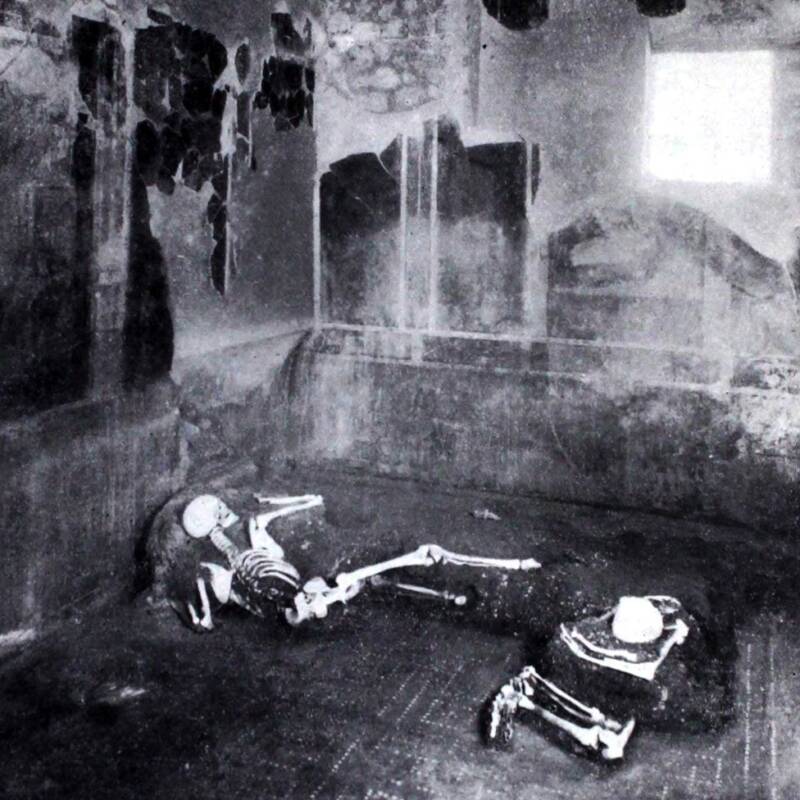

The man in question was found in a building known as the House of the Craftsman, CNN reported. Archaeologists discovered him slumped inside the dining room beside an older woman back in the early 1930s. Her remains contained gaps in the genome, while his were perfectly preserved — and offered staggering revelations.

While Pompeii is one of the most thoroughly studied archaeological sites in the world, garnering genetic evidence from its victims hasn’t been easy. As published in the Scientific Reports journal, this study showed the man in question was 35 to 40 years old — and likely didn’t run from the eruption because he had spinal tuberculosis, or Pott’s disease.

“Pompeii is one of the most unique and remarkable archaeological sites on the planet, and it is one of the reasons that we know so much about the classical world,” said Gabriele Scorrano, lead author of the study. “To be able to work and contribute in adding more knowledge about this unique place is unbelievable.”

Serena VivaDr. Serena Viva analyzing the remains.

The eruption of Mount Vesuvius was biblical in its proportions and terrifying to behold. When the volcano in southern Italy exploded, a 10-mile mushroom cloud of ash and pumice saw thousands in Pompeii and nearby Herculaneum suffocate from toxic gas — and stay buried until the 1700s.

While 2,000 sets of remains have since been unearthed from the destroyed city, most of what is known about the cataclysm stems from an account by Pliny the Younger. Fortunately, the advent of modern technology has turned those tides.

The two Pompeiians in question were first discovered in 1932 and 1933. Found in the corner of their dining room, it looked as though they had only just eaten lunch. University of Salento anthropologist Dr. Serene Viva explained that “the answer to why they weren’t fleeing could lie in their health conditions.”

Indeed, she found bacteria known to cause tuberculosis in the man’s DNA. A professor in the department of health and medical sciences at the University of Copenhagen, Scorrano was stunned to see such a tiny amount of bone powder reveal so much.

Serena VivaThe Pompeii victim was 35 to 40 years old and suffered from tuberculosis.

“It was all about the preservation of the skeletons,” said Scorrano. “It’s the first thing we looked at, and it looks promising, so we decide to give [DNA extraction] a shot … New sequencing machines can [read] several whole genomes at the same time.”

Their findings also shed light on the diversity of the Pompeiian’s hometown. While the DNA extracted from his skull showed he shared genetic markers with others who lived in Ancient Rome, he also had genes commonly found in people from Sardinia.

“It is significant because it shows that there is a lot we still don’t know about the genetic diversity act the time of the Roman Empire, and how this impacts modern Italians and other Mediterranean populations,” explained Scorrano.

The scientists compared the man’s DNA with 1,030 of his contemporaries and found that 471 of them were western Eurasian. This suggested that there was substantial genetic diversity in populations around the Italian Peninsula at the time.

Scientific ReportsThe DNA was extracted from the fourth lumbar vertebra from the back of the man’s skull.

Before this study, only small amounts of mitochondrial DNA from human or animal remains of Pompeii were sequenced. Most skeletal evidence had been destroyed by nature itself, as oxygen in the atmosphere led to decomposition. Fortunately, however, the gas, lava, and debris of Pompeii protected this DNA from doing so.

“One of the main drivers of DNA degradation is oxygen,” explained Scorrano. “Temperature works more as a catalyst, speeding up the process. Therefore, if low oxygen is present, there is a limit of how much DNA degradation can take place.”

There’s a lot of research left to be done regarding the lives and deaths of those who lived in Pompeii nearly two millennia ago. For Scorrano, the genome-sequencing was a major piece of the puzzle, and taking “part in a study like this was a great privilege.”