Whether mummies that were preserved naturally or those that were intentionally embalmed, these stories are as fascinating as they are unsettling.

Martin Bernetti/AFP via Getty ImagesThe Chinchorro mummies are over 7,000 years old, making them some of the oldest in the world.

The ancient Egyptians are perhaps the most well-known group of people to have used mummification to preserve their dead. They placed the bandage-wrapped corpses of their rulers in elaborate tombs, along with items that the deceased would supposedly desire in the afterlife.

But while Egyptian mummies are certainly some of the most fascinating examples of the mummification process on Earth, they are not the only cases of ancient embalming and preservation. Nor are they the oldest.

In fact, some mummies found in modern-day Chile and Peru predate Egyptian mummies by several centuries. And then, of course, there are more recent mummies, some of which had been preserved by nature.

From Ötzi the Iceman to the “screaming” mummies of Guanajuato, these are some of the most well-preserved mummies from across the globe.

The Chinchorro Mummies: The 7,000-Year-Old Corpses In Modern-Day Chile And Peru

Creative Touch Imaging Ltd./NurPhoto via Getty ImagesThe Chinchorro mummies predate Egyptian mummies by about 2,000 years.

Thousands of years ago, the ancient Chinchorro people lived in modern-day Chile and Peru. According to National Geographic, their culture eventually developed a strong emphasis on fishing — and mummification.

The Chinchorro people are one of the oldest groups to have intentionally preserved humans through mummification around 7,000 years ago. And their process of mummifying the deceased was incredibly elaborate.

First, they would dismember the body piece by piece before removing all of the body’s internal organs and pulling the brain from the skull. They would also strip the body of its flesh using stone tools. Once the cadaver was dry, the ancient morticians would stuff the remains with natural materials like sticks and reeds. Then, they would reattach the person’s skin.

Finally, the Chinchorro would adorn the corpse with wigs, clay masks, and paint. One of the most common colors of paint used was black. However, other mummies were painted red (these mummies were less likely to be completely dismembered during mummification and instead had incisions made all over their bodies to take the organs out, according to CNN.)

Martin Bernetti/AFP via Getty ImagesThe Chinchorro culture likely inhabited the coasts near the Atacama Desert between 7000 and 1500 B.C.E.

But while we have a thorough understanding of the process itself, no one is quite sure why the Chinchorro mummified their dead. Naturally, it could have been for ritualistic reasons, but others suggest that natural disasters may have inspired the Chinchorro to worship their ancestors.

According to Smithsonian Magazine, more than 280 Chinchorro mummies have been found since their initial discovery in 1917. Today, about 100 of these mummies are on public display in an exhibition space.

What may be most curious about the Chinchorro mummies is that, unlike other cultures, status seemed to play no factor in whether or not someone was preserved. People of all social statuses and family placements were mummified. Apparently, the Chinchorro didn’t bury their dead.

Some archaeologists even suggest that to the Chinchorro people, the mummified bodies were art, as they didn’t leave behind any pottery or creative tools. As University of Tarapacá anthropologist Bernardo Arriaza said, “The body becomes a kind of canvas where they express their emotions. The Chinchorro transform their dead into genuine works of pre-Hispanic art.”

The Qilakitsoq Mummies: The Inuits Who Were Naturally Freeze-Dried In Greenland

Werner Forman/Universal Images Group/Getty ImagesA Qilakitsoq female mummy’s tattoo, which researchers believe signified her tribal membership and marital status.

While hunting grouse in Greenland in 1972, brothers Hans and Jokum Grønvold came across a shallow cave. There, they found eight bodies stacked vertically. The corpses were so incredibly well-preserved that the brothers thought they were looking at a burial that had happened recently.

After they reported the site to authorities, however, archaeologists investigated the site and discovered that the bodies were about 500 years old. The people likely died in 1475 C.E. near the abandoned Inuit settlement of Qilakitsoq, earning them the name the “Qilakitsoq Mummies.”

Experts also found that the cold temperatures of the Nuussuaq Peninsula in northwestern Greenland had essentially “freeze-dried” the bodies, keeping most of their organs intact and the tattoos on their skin still visible.

Of all the bodies, the best preserved was that of a six-month-old infant who was likely buried alive. Researchers have theorized that the preservation was due to the baby’s small size, as the body would have frozen quickly.

Werner Forman/Universal Images Group/Getty ImagesThe six-month-old Qilakitsoq child preserved through natural mummification.

Archaeologists later learned that three of the adult bodies in the grave had been sisters. Buried with them, along with the infant, were an 18-year-old girl, and a boy who was about two to four years old.

The bodies offered significant insight into Thule Inuit culture.

They were heavily infested with lice, their intestines full of moss, and their lungs filled with soot. This implied that they supplemented their meat-heavy diets with plants and likely breathed in the soot due to lamps that were lit by seal oil in their homes. The lice, it seems, leaped from their bodies to their food as they ate, since some of the lice were found in their intestines.

There are also Norse records of trades with the Thule Inuit around 1200 C.E., though these trade deals, of course, sometimes turned violent.

One such account from Norse traders peculiarly noted, “When [the Inuits] are struck by weapons, their wounds are white, with no flow of blood… but when they die, the bleeding is almost endless.”

Ötzi The Iceman: The Ancient Murder Victim Found In The European Alps

Sven Hoppe/picture alliance via Getty ImagesÖtzi’s body was so well-preserved that he looked like a mountaineer who died in modern times.

On September 19, 1991, two German hikers named Helmut and Erika Simon were trekking through the Austro-Italian Alps when they found a corpse in the ice. They alerted Austrian rescue workers, who believed the body belonged to a mountaineer who had died recently. A series of careless excavation procedures then led to some damage to the corpse.

But medical experts in Austria eventually realized the rescue workers’ error. As it turned out, the corpse was quite far from recently deceased. Ötzi the Iceman, as he came to be known, was actually a 5,300-year-old Neolithic man — one of the oldest preserved bodies in history.

While most mummies are preserved by drying out the corpse in some way and secluding it from environmental factors, Ötzi is considered a “wet” mummy. His body was perfectly preserved, frozen in the ice, and the humidity of the glacier kept his organs and skin intact.

The strange, immaculate preservation allowed researchers to essentially perform a modern autopsy on Ötzi. This offered significant insight into what the man’s life had been like way back in the Copper Age.

Paul Hanny/Gamma-Rapho via Getty ImagesGerman tourists Helmut and Erika Simon had found Ötzi with his head and shoulders protruding from the ice.

They were able to determine that Ötzi was in his 40s when he died, that he had weighed roughly 110 pounds, and that he stood about five feet, three inches tall, according to Live Science. He had intestinal parasites, stomach ulcers, and arthritis, and he might have been lactose intolerant.

Ötzi shared a genetic affinity with people who came from the Mediterranean islands of Sardinia and Corsica. He also had 61 tattoos, made by rubbing charcoal into small cuts across the surface of his skin.

But while researchers have gained a wealth of information from studying Ötzi’s body, the question of how, exactly, he died still remains somewhat of a mystery. Many believe that he was murdered — because there was an arrowhead lodged in his left shoulder. His belongings hadn’t been taken, suggesting this murder may have been of a personal nature.

Of course, there’s no way of knowing for sure, given that any witnesses or suspects have been dead for well over 5,000 years.

Today, Ötzi is stored in a freezer at the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology in Bolzano, Italy, where countless people remain in awe of his remains.

The Egtved Girl: The “Bronze Age Bride” Who Was Buried In A Peat Bog In Denmark

The National Museum of DenmarkThe Egtved Girl’s final resting place, an oak coffin that was uncovered near the village of Egtved in Denmark.

In 1921, researchers at an archaeological site near Egtved in Denmark unearthed the ancient remains of a teenage girl within a burial mound of thick peat bog. The remains, which dated back to 1370 B.C.E., were buried with an ox hide and a woolen blanket in an oak coffin.

But according to Ancient Origins, although the blanket held the girl’s shape, much of her actual body was gone. However, certain body parts had been preserved very well, including her fingernails, hair, and scalp.

This strange and eerie preservation, scientists said, is the result of a microclimate caused by the region’s soil. As rainwater seeped into the hollowed-out oak coffin, it created an oxygen-starved environment that, over the course of several centuries, decayed her bones entirely.

Still, the finding caused quite a stir in Denmark in the 1920s, and the ancient teen soon came to be known as the “Egtved Girl.”

Also buried with her were the ashes and bones of a young child, believed to be around five or six. But no identity has been attached to them, leaving the child’s relationship to the Egtved Girl somewhat of a mystery.

Among the clothing items that remained were a large, bronze belt disc, bronze pins, and a hair net. Local flowers rested on top of the coffin alongside a small bucket of beer made from honey, wheat, and cowberries.

The National Museum of DenmarkThe Egtved Girl was believed to have been slender, blonde, and of high social status.

Then, in 2015, researchers studying the girl’s remains made a remarkable discovery: The girl wasn’t from the Denmark region at all.

New information revealed that the girl — who, at an age between 16 and 18, would have likely been considered a woman in her time — may have actually hailed from the Black Forest of modern-day Germany. She probably traveled between the Black Forest region and the Egtved region in her final years.

Now known as a “Bronze Age bride,” the girl was likely sent to the Egtved region to marry a chieftain there, according to Archaeology Magazine.

This may also offer some insight into the identity of the child buried with her.

As Kristian Kristiansen of the University of Gothenburg explained, “Dynastic marriages were often followed by an exchange of ‘foster brothers’ to secure the alliance.” The ashes of the child, then, would have either belonged to a boy from the Black Forest region or from the Egtved region, who was meant to be exchanged with a different boy from the other tribe.

The “Screaming” Mummies Of Guanajuato: The Horrifying Remains Of Cholera Victims In Mexico

George Pickow/Three Lions/Getty ImagesMummies on display in the Panteon cemetery vault in Guanajuato, Mexico.

In the Mexican town of Guanajuato, the 1850s cholera epidemic wreaked havoc on those who lived there. So many people died that the bodies had begun to quite literally pile up, forcing townsfolk to forego burying their dead and instead place them in above-ground crypts — but the warm, arid environment caused the partially-embalmed corpses to start mummifying.

And in 1865, local authorities instituted a “burial tax” that forced families to make continual payments in order to keep their relatives underground. Those who couldn’t afford the tax had to stand by and watch as their loved ones were pulled out of the ground and moved into the crypts.

It was then that the crypt owners found the mummified bodies in the crypts, their faces forever frozen in expressions that look like screams.

And as the crypt owners took a closer look at the “Guanajuato Mummies,” they soon made several more horrifying discoveries.

One body, that of Ignacia Aguilar, had been found biting into her own arm. Many believe she had accidentally been buried alive after her cholera symptoms and other health conditions made her appear dead.

Three Lions/Getty ImagesMummified infants in Guanajuato, Mexico.

Another belonged to a woman who died in childbirth. Her 24-week-old fetus had also been mummified — one of the youngest mummies in existence.

The mummies became so well known that 111 were put on display by the early 1900s. And 59 are still on display today at El Museo de las Momias.

But despite the years passing, the horror of the mummies’ faces hasn’t faded. In 1947, nearly a century after the cholera epidemic, author Ray Bradbury visited a crypt in Guanajuato and could barely stomach the sight.

“The experience so wounded and terrified me, I could hardly wait to flee Mexico,” he said. “I had nightmares about dying and having to remain in the halls of the dead with those propped and wired bodies.”

The Guanche Mummies: The Mysterious Corpses Found On The Canary Islands

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty ImagesMummified remains of a Guanche male at the National Archaeological Museum in Madrid, Spain.

The history of the Canary Islands — an archipelago that’s part of Spain but located much closer to the coast of Morocco — is still mysterious to researchers. It was once inhabited by the Guanches, a pre-colonial Indigenous people. But much of their way of life has been lost to time.

However, several Guanche mummies found in the caves on the Canary Islands are helping researchers uncover more of the islands’ history. These mummies are also helping experts separate fact from fiction.

According to National Geographic, researchers are hoping to learn more about the fabled Barranco de Herques, a “ravine of the dead” that allegedly houses the “cave of the thousand mummies.”

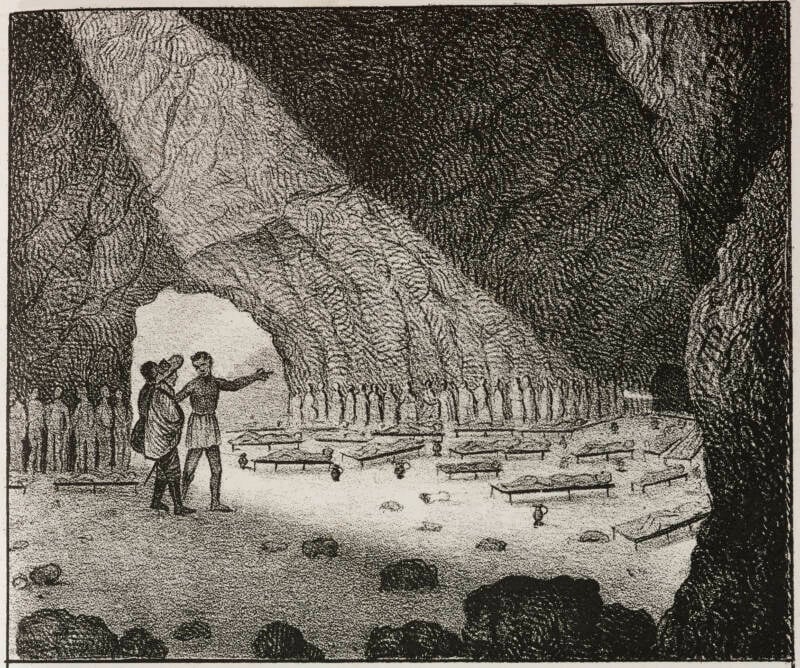

The story goes that, in 1764, Spanish regent Luis Román entered a cave within a gorge on Tenerife, the largest of the Canary Islands. There, he discovered, as the writer José Viera y Clavijo described, “a wonderful pantheon… So full of mummies that no less than a thousand were counted.”

De Agostini Picture Library via Getty ImagesA cave filled with the Guanche mummies in the Canary Islands. Lithograph by Giuseppe Antonelli in 1838.

Most archaeologists agree that the description of “a thousand mummies” was an exaggeration, but it’s likely that there were hundreds of mummies hidden within this mysterious cave (with no recorded coordinates).

Local lore also maintains that a large sepulchral cave exists on the islands, housing the remains of the Mencey kings, the islands’ pre-colonial rulers.

While no distinct Guanche populations exist today, the few mummified corpses that archaeologists have managed to extract from the caves of the Canary Islands are helping to illuminate the history of the people — especially in regard to how they honored their dead.

The Guanche mummies — called xaxo — were treated with dry herbs and lard before being left to dry in the sun. Once dried, the body was smoked by a fire. In total, the process took a little over two weeks, and then the family of the deceased would place the body in a stitched animal hide bag.

Remarkably, Guanche mummies were very well-preserved, especially compared to their Egyptian counterparts. Many of their organs remained intact, preserved within their bodies thanks to a mixture of minerals, herbs, bark, and resin from dragon trees that prevented decay.

Javier Carrascoso, associate chief of radiology at Madrid’s QuirónSalud University Hospital, told National Geographic that one Guanche mummy had been so well-preserved that “it looked like a wooden sculpture of Christ.”

Unfortunately, the cave of a thousand mummies still remains elusive to archaeologists in the region. Some believe it may have been lost to a cave-in or, more likely, plundered when the islands were colonized.

Xin Zhui: The 2,000-Year-Old Chinese Mummy Whose Veins Still House Blood

Public DomainXin Zhui, or Lady Dai, died of a heart attack in 163 B.C.E. just moments after eating some melon.

In 1971, workers digging near an air raid shelter in Changsha, China unearthed a massive Han Dynasty tomb containing more than 1,000 stunning artifacts, including makeup, toiletries, lacquerware, and wooden figures.

It also contained the mummified corpse of Xin Zhui, also known as Lady Dai, whose head was still covered in hair, whose skin was soft to the touch, and whose ligaments could still bend much like a person who is still alive.

Despite being more than 2,000 years old, dying in 163 B.C.E., she was in a similar condition to that of a person who had died recently. Incredibly, scientists were able to perform an autopsy on her.

They found that Type-A blood was still in her veins, and they could even identify an official cause of death for the woman: a heart attack.

Sadly, once her skin came into contact with oxygen, she began to decompose. Pictures of her current condition don’t quite do her justice.

DeAgostini/Getty ImagesAn illustration depicting the burial chamber in which Lady Dai was placed.

Still, she remained in near-perfect condition for about two millennia, and researchers attribute that amazing feat to the airtight seal of her tomb.

She had been sealed away in a small pine box, which was in turn placed inside three increasingly larger pine boxes. Her body had also been wrapped in 20 layers of silk and soaked in 21 gallons of a slightly acidic “unknown liquid” that was found to have traces of magnesium in it.

The chamber was also packed with charcoal to absorb moisture and sealed with clay. This ensured that oxygen and decay-inducing bacteria would be unable to penetrate the coffin and get to the corpse. Additionally, the top of the tomb was sealed with three feet of clay, keeping water out.

But despite the immaculate preservation of her body, we know little about her life. Researchers know that Lady Dai was the wife of a high-ranking Han official named Li Cang and that she died around age 50. Her heart attack was likely brought about by obesity, lack of exercise, and over-indulgence.

Beyond that, all that remains of her is her corpse.

The Tollund Man: The 2,400-Year-Old Sacrificial European Bog Body

Werner Forman/Universal Images Group/Getty ImagesThe Tollund Man was one of many “bog bodies” found in a peat bog in Denmark.

In 1950, two Danish brothers were collecting peat in a bog near Silkeborg. But buried within the peat was something terrifying — a human body so well-preserved they believed the man had recently been murdered.

When police investigated, however, they found that the body had been buried beneath six feet of peat, with no signs of recent digging. After they turned the body over to archaeologists, radiological tests revealed that the man had actually died well over 2,000 years ago, between 375 and 210 B.C.E.

As it turned out, the “Tollund Man” — named after the village that the Danish brothers were from — had been a victim of human sacrifice.

For centuries, people have been unearthing bog bodies — often victims of human sacrifice or execution — who were naturally preserved by the acidic water, low temperatures, and scarce oxygen in peat bogs.

Through the ages, this combination has helped preserve the bodies’ hair, fingernails, and even some of their internal organs.

Wikimedia CommonsAnother bog body, Windeby I, a teenage boy found near Schleswig, Germany.

But the Tollund Man is one of the most well-preserved. Eerily, the noose that was used to hang him still sat around his neck.

While each of the bog bodies has its own unique story, researchers have come to understand that to Iron Age societies, the bogs were important spiritual sites. And it’s believed that hanging people as a sacrifice was done in order to ensure a bountiful harvest for the season.

However, there are many bog bodies of people who had been stabbed, bludgeoned, beaten, and strangled to death as well.

Not all mummies, it seems, were honorably preserved.

Juanita: The Inca “Ice Maiden” In Peru

Gourami Watcher/Wikimedia CommonsMummy Juanita, also known as the Lady of Ampato, wrapped in the bundle where she was found in Peru.

In 1995, anthropologist Johan Reinhard and his climbing partner Miguel Zárate ascended Mount Ampato, a stratovolcano in southern Peru. Recent volcanic activity had warmed the snow near the top of the mountain, causing certain snow patches to move downward.

It just so happened that within one of these melting snow patches was the burial site of an Inca girl, roughly 12 to 15 years old. Her wrapped body had been astoundingly well-preserved by the thin, cold air near the summit.

There, Reinhard and Zárate found the young mummy now known as Juanita, or the Lady of Ampato. Reinhard later recalled that many doctors who saw the mummy couldn’t believe that she was over 500 years old. Many said she was preserved so well that she could have died weeks earlier.

She didn’t, though. She died sometime between 1450 and 1480 C.E., as part of capacocha, a sacrificial rite among the Inca that involved killing children.

Capacocha was done to appease the gods, with the hopes of preventing a natural disaster or ensuring a fruitful harvest. And Juanita’s placement atop Mount Ampato was likely part of the Inca’s mountain worship.

Using DNA from Juanita’s hair, scientists constructed a timeline of her final days. Markers in her hair indicated that up until a year before her death, she lived on the typical Inca diet of potatoes and vegetables.

Jaime Razuri/AFP via Getty ImagesJuanita was put on display in Japan in 1999.

However, closer to her death, her diet shifted and she was fed more luxurious foods such as animal protein and maize. She was also given large quantities of coca and alcohol — these last two were commonly given to victims of child sacrifice to put them in a heavily intoxicated state.

The Inca adjusted this drug mixture so that child sacrifices would fall asleep in the cold mountains. But tragically, Juanita did not die in her sleep.

Damage to her skull shows that she had died from a hemorrhage. Juanita was likely struck in the back of the head with a club, which caused her blood to swell and her brain to shift positions in her skull.

Still, Juanita’s mummified body remains one of the most curiously well-preserved in history, with her skin mostly intact. She can still be seen on display at the Museo Santuarios Andinos in Arequipa, Peru.