Researchers have sequenced the first complete mitochondrial genome of an ancient Phoenician. The results of the studies of the remains of a man called the “Young Man of Byrsa” and “Ariche” has linked him to a very early and rare haplogroup found in Europe.

GenomeWeb reports that the Young Man of Byrsa had a mitochondrial genome “from the haplogroup U5b2c1, considered to be one of the most ancient haplogroups in Europe, and associated with hunter-gatherer populations. The U5b haplogroup is thought to have arisen in Europe between 20,000 and 24,000 years ago.”

Lisa Matisoo-Smith of the University of Otago in New Zealand and co-leader of the study said in a statement “While a wave of farming peoples from the Near East replaced these hunter-gatherers, some of their lineages may have persisted longer in the far south of the Iberian peninsula and on off-shore islands and were then transported to the melting pot of Carthage in North Africa via Phoenician and Punic trade networks,”.

The U5b haplogroup is considered to be rare in modern populations – all of the reported carriers are of European ancestry and from Spain, Portugal, England, Ireland, Scotland, the US, and Germany. As professor Matisoo-Smith told Phys.org: “It is remarkably rare in modern populations today, found in Europe at levels of less than one per cent. Interestingly, our analysis showed that Ariche’s mitochondrial genetic make-up most closely matches that of the sequence of a particular modern day individual from Portugal.”

This is something of a surprise for the researchers, who wrote in the journal PLOS One “Though it is believed that Carthage was established by colonisers from Tyre, in what is today Lebanon, it is unlikely that our Phoenician young man had maternal ancestry that traced back to this founding population […] as the haplogroup U5b2c has not been identified in our modern Lebanese samples or in ancient (early Neolithic, PPNB) remains from the Levant.”

The skeleton of the Young Man of Byrsa that was found in Carthage. (Public Domain)

The remains of “Ariche” were discovered in 1994 at Byrsa Hill when a gardener happened upon his tomb while preparing to plant a tree for the National Museum of Carthage. Byrsa Hill is located in Tunisia, at a site which was once a Phoenician acropolis.

District of Punic Byrsa in ancient Carthage, Tunisia. (CC BY SA 3.0)

According to the American University of Beirut (pdf), the young man’s tomb held “2 sarcophagi carved in the sandstone. The left tomb contained the skeleton of a young man lying on his back, his arms bent on his abdomen. The sarcophagus to the right was empty.”

The young man of Byrsa was described as a “robust young man around 1m70 [5.58ft.] high, with a long skull, broad forehead, and a squarish chin.” He was estimated to be between 19-24 years old when he died. Punic inscriptions called him Arish “the beloved one.”

Some of the objects found with the remains included two Punic amphorae, a Punic lamp, bones of a sacrificial goose, and some small Egyptian type ivory amulets. These and other artifacts helped to date the tomb to around 500 BC.

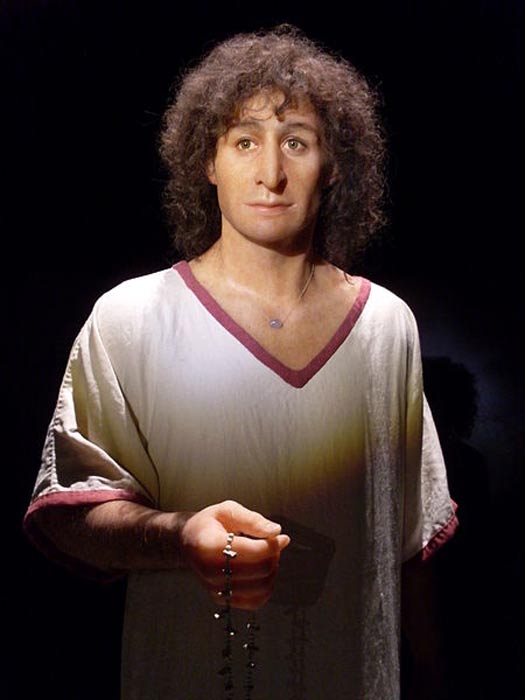

Reconstruction of the Young Man of Byrsa. (Public Domain)

The new study helps provide a little more information about the influential and relatively mysterious Phoenicians. It is known, however, that “The Phoenicians were the direct descendants of the Canaanites of the south Syrian and Lebanese coast who, at the end of the second millennium BC, became isolated by population and political changes in the regions surrounding them.”

Despite the fact that Phoenicians were so well-known in the ancient world and they have been acknowledged for their links to the early Greek alphabet, there are few of their own written texts that have survived the passing of time. This lack of information has led modern historians to mostly rely on Egyptian, Assyrian, Babylonian, Greek, and Roman sources for data on the ancient people.