The discovery of a cavern filled with artifacts in Glozel, France in 1924 was an astonishing find. Initially brought to light by a farmer plowing his fields, the cavern yielded more than 3,000 artifacts over the course of 6 years. The artifacts quickly became a great source of controversy when experts began to debate their authenticity. To this day, the Glozel artifacts are still controversial, as there has never been a universal acceptance as to whether they are authentic.

The discovery of the Glozel artifacts was completely unintentional. They were not discovered by scientists conducting an excavation or as a part of any planned recovery. Rather, the discovery came from very modest means. On March 1, 1924, 17-year-old Émile Fradin was plowing a field on his farm with a cow-drawn plow. As he was plowing, the cow’s foot got stuck in the ground. As Fradin tried to free the cow’s foot, he discovered an underground chamber. Within the chamber were human bones and ceramic pieces. The walls were made of clay bricks, and the floor was tiled. The young man realized that he had found something significant, worthy of a scholarly review.

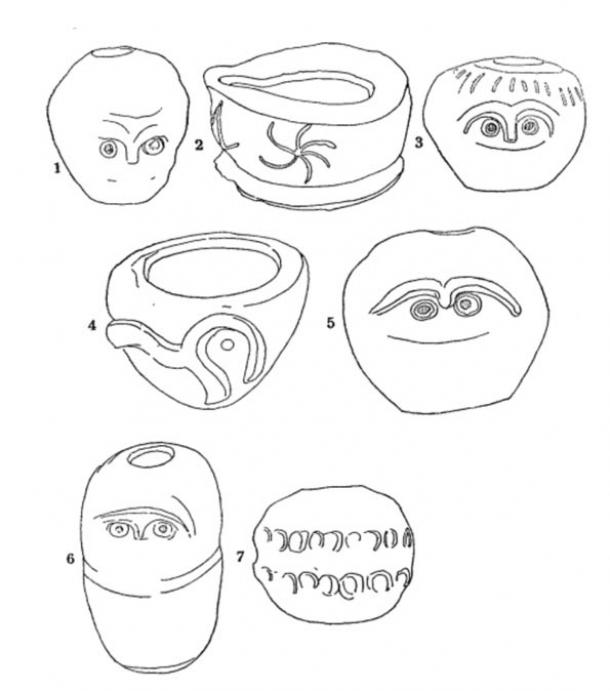

Detail, Artifacts from the Glozel chamber. France, 1920s. Public Domain

The first academics to view the chamber were Adrienne Picandet, a local teacher, and Benoit Clément, from the Société d’Émulation du Bourbonnais. Clement and a man named Viple later returned to the site with a pickaxe. They removed the chamber walls and took them with them. Sometime later, Viple contacted Fradin and informed him that the chamber was a Gallo-Roma site dating back to 100-400 A.D. Viple indicated that the site may be of some archaeological importance. A museum was created to hold the artifacts.

Young Émile Fradin inside his museum at Glozel. Allier, France. 1920s. Public Domain

Artifacts in the Glozel museum. 1920s. Public Domain

Word of the discovery of the chamber soon spread, thanks to a publication in the Bulletin de la Société d’Émulation du Bourbonnais. As word spread, more researchers were drawn to the Fradin farm. Physician and amateur archaeologist Antonin Morlet visited the site. He offered 200 francs to be permitted to excavate the site. Excavations began on May 24, 1925, with Morlet eventually uncovering a variety of artifacts including inscripted tablets, bones, engraved stones, and flint tools. After completing his excavations, Morlet identified the items as dating back to the Neolithic period, from 10,200 B.C. until 2,000 B.C. Morlet’s findings were published in an article titled Nouvelle Station Néolithique, of which Fradin was listed as a co-author. Clearly, Morlet’s dating of the chamber and artifacts extended much further back than Viple’s dating. But dating of the Glozel artifacts proved not to be the only issue in contention, as there were some who doubted the legitimacy of the site as a whole.

Doubts about the authenticity of the Glozel find began upon the publication of Morlet’s report. Having been authored by Morlet, an amateur archaeologist, and Fradin, a peasant farmer, French archaeological academia skeptically dismissed the report. Further excavations of the site ensued. The curator of the National Museum of Saint-Germain-en-Laye at the time, Salomon Reinach, conducted a 3-day excavation. He concluded that the site was authentic in a writing published in the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. Another famous archaeologist, Abbé Breuil, excavated the site with Morlet. While Breuil was impressed with the site, he ultimately concluded that “everything is false except the stoneware pottery.”

Excavation at Glozel. 1920s. Public Domain

With such opposing conclusions being drawn as to the dating and authenticity of the Glozel artifacts, the topic quickly became very controversial. The International Institute of Anthropology in Amsterdam held a meeting in September 1927 where the Glozel controversy was a hot topic of discussion and debate. The Glozel artifacts could have represented a major historical find that might provide insight into ancient human cultures, or it could have been merely a hoax. It was important to determine the truth to preserve the accuracy of the modern world’s interpretations of human history. Ultimately, a commission was chosen to further investigate Glozel. On November 5, 1927, they began a 3-day excavation. By this point, spectators were visiting the site in large numbers, curious as to what secrets would be uncovered and what discoveries would be made. The interest of the spectators was further fueled as the commission found new artifacts during excavation. However, the final conclusion of the commission was that almost everything found at Glozel was a fake. Only a few flint axes and pieces of stone were declared to be authentic.

Stone or clay tablets and other artifacts in the Glozer museum. 1920s. Public Domain

Sketches of inscriptions on the Glozel tablets and artifacts. Public Domain

Legal battles began to arise at this point. Fradin was accused of forgery by René Dussaud, curator at the Louvre. Fradin filed a defamation lawsuit against Dussaud, adding further fuel to the ongoing controversy. Glozel was visited again in February 1928, this time by Felix Regnault, who was serving as the president of the French Prehistoric Society at the time. Regnault filed a fraud claim against Fradin. At Regnault’s direction, police raided the Glozel museum, where artifacts had been on display. They confiscated three cases of artifacts.

In hopes of settling the growing disputes, a new set of archaeologists, known as the Committee of Studies, was appointed to conduct another excavation at Glozel. After working for two days in April 1928, the Committee found several additional artifacts. They ultimately concluded that the site was authentic, and that it dated back to the Neolithic period, just as Morlet had concluded.

Sketches of pottery found at Glozel. Public Domain

Since the 1920s, controversy as to the authenticity of the Glozel site has remained. Studies of the area slowed as private excavations were outlawed from 1941 through 1983. The site was re-excavated in 1983, but the full report for that excavation was never released. In 1995, a 13-page summary was published, in which the site and some of the artifacts were estimated to date back to medieval times, at approximately 500-1,500 A.D., but that it was likely that many of the artifacts found were forgeries. The controversy and curiosity continues to this day, as modern testing has allowed for a more accurate dating of some of the pieces. This advanced testing has shown that many Glozel artifacts are, in fact, authentic. However, the overall authenticity of the site is still in question. A group of scholars holds an annual colloquium about Glozel in hopes of one day determining the authenticity of the site and artifacts for once and for all. However, one key player in the controversy will no longer provide any insights, as Fradin passed away in 2010, at age 103. If he held any remaining secrets as to the site’s authenticity, he took those to the grave with him. For now, it is still not entirely certain if the Glozel site is an amazing historical find, or an elaborate hoax.